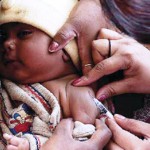

Indian billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla, founder of the world’s biggest maker of vaccines, will cut the price of polio immunisation and introduce shots for diarrhoea and pneumonia, undercutting Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline.

Indian billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla, founder of the world’s biggest maker of vaccines, will cut the price of polio immunisation and introduce shots for diarrhoea and pneumonia, undercutting Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline.

Mr Poonawalla, who set up the Serum Institute of India in 1966, will use last year’s acquisition of a Dutch vaccine business. The injectable form of polio inoculation will be added to the oral drops the Pune, India-based company supplies to organisations such as the United Nations Children’s Fund, he said.

The closely held group also plans to sell a low-cost pneumococcal shot to compete with Pfizer’s $4bn Prevnar pneumonia vaccine by 2016.

The plan by the Serum Institute, which says it supplies vaccines used to immunise two out of three children worldwide, will “revolutionise” efforts to eradicate polio that affects nerves and results in paralysis, said Bruce Aylward, assistant director-general at the World Health Organisation (WHO). The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a key funder of the effort to exterminate the malady, has backed the proposal, as oral drops, made of live virus, carry the risk of infection.

“On May 30, Mr Gates came over for a private dinner at my house,” and asked that Serum Institute remain family-owned, Mr Poonawalla said in an interview. “The obvious reason was that, as soon as we sell the company, ‘big pharma’ would immediately double the price of vaccines.”

Mr Poonawalla bought Bilthoven Biologicals six months ago to gain technology, expertise and manufacturing facilities in the Netherlands. The facility makes an injectable vaccine based on an inactive form of polio virus developed by Jonas Salk in the 1950s, and is one of four facilities in the world with the capability, according to Martin Friede, a scientist at the WHO in Geneva.

“We decided to go in for the acquisition of this plant with the encouragement of the Gates Foundation,” Mr Poonawalla said.

“This plant would be scaled up for production, as we have done in all our other vaccines, to give 100% of the requirement to the rest of the world,” he said.

London-based Glaxo and Paris-based Sanofi are the largest suppliers of injectable polio vaccine, which is used in most developed countries to protect children against crippling poliomyelitis. Developing countries such as India use the oral formulation developed by Albert Sabin, which contains live, weakened virus that is easier and cheaper to administer.

India, the world’s second most populated nation, has not reported a polio infection since January 2011, according to government data, while neighbour Pakistan is close to eliminating a strain of the virus.

Occasionally, the Sabin virus mutates back to a virulent strain and sparks immunisation-derived polio outbreaks. That risk will deter governments and UN agencies from using the Sabin vaccine as the world comes closer to eradicating polio, requiring a switch to injected products based on inactivated polio virus, Mr Poonawalla said.

The company “could really revolutionise the polio endgame”, said Mr Aylward. “They are potentially the most exciting game in town.”

The Serum Institute will enter the injectable polio vaccine market with a shot costing as little as €0.70 in multidose vials, Mr Poonawalla said. That compares with about €2.50 per shot now.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a contract with Sanofi ending in March to buy e-IPV, an enhanced-strength injectable polio vaccine, at $12.24 a dose, the Atlanta-based agency says on its website.

The company’s strategy of not spending on advertisements and waiting for demand for the vaccines to increase has helped it control costs, Mr Poonawalla said. Serum Institute typically enters vaccine markets about five years or longer after a new product has been released, demand is well established and patent protection has ended.

“We’re going to follow the Serum Institute’s philanthropic policy of just putting it at half the price,” said Mr Poonawalla, who also runs two hotels in the UK and an airline charter service in India. “So we can’t see any competition coming our way.”

The price of injectable polio vaccine may be lowered further by the use of additives, called adjuvants, that boost potency, he said.

Trevor Mundel, president of the global health programme at the Gates Foundation, said: “Vaccine manufacturers in developing countries, like the Serum Institute of India, are critical to bringing down vaccine prices.”

Sanofi Pasteur, the vaccine unit of France’s largest drug maker, is well positioned to face competition from Indian manufacturers with its Hyderabad-based unit, Shantha Biotechnics, said Olivier Charmeil, president and CEO of the unit.

Shantha produces shots for hepatitis B for emerging markets, tetanus shots for Unicef, and cholera vaccines for Haiti and Africa. The company’s Shan6 inoculation will be an “affordable answer” to six diseases, including polio, Mr Charmeil said.

“Shantha allows us to manufacture vaccines with the right quality standards at affordable prices,” Mr Charmeil said.

Shantha, which is developing immunisations for diarrhoea and cervical cancer, will fuel Sanofi Pasteur’s growth in emerging markets, he said.

Glaxo spokesman David Daley declined to comment on competition from low-cost manufacturers. The company’s shares fell 0.3% to 1,401p in London.

The Gavi Alliance, which buys vaccines for children in poor nations, and the Gates Foundation are encouraging the Serum Institute to supply the shots at a third to a quarter of the cost, Mr Poonawalla said.

“The Serum Institute has already demonstrated the impact its high quality, low-cost vaccines can have on some of the world’s poorest communities,” said Seth Berkley, CEO of the Gavi Alliance.

Source: BDLive