Pfizer just completed a major step in its Phase 3 trials for a Lyme disease vaccine. Several other tick-borne illness vaccines are in the early stages of development.

Cases of Lyme disease, the tick-borne illness that can cause chronic fatigue and body aches, have tripled in the United States over the past three decades — and that’s likely a massive undercount.

“What gets reported is the tip of the iceberg,” said Chantal Vogels, a research scientist who studies vector-borne viruses at the Yale School of Public Health.

New England is the most “ticky” region of the country, and states here consistently have among the highest rates of Lyme disease nationally. Warmer winters due to climate change, more trees, a growing deer population, and humans pushing into the suburbs where they’re in more frequent contact with nature, have all contributed to the growing prevalence of tick-borne disease.

Yet in the face of big tick-borne disease numbers, there is still no vaccine available to the public two decades after the first Lyme vaccine was discontinued.

Still, several promising efforts are underway to prevent Lyme and other tick-borne diseases — or even to stop tick bites altogether, said infectious disease experts. One Lyme vaccine contender from Pfizer, the company that manufactured one of the COVID-19 vaccines, is ahead of the pack and could be available as early as 2026, pending final trials and regulatory approval.

Though researchers are working on a vaccine for pretty much every tick-borne disease in the United States, the vast majority are in very early stages, said Samuel Perdue, chief of basic sciences, bacteriology, and mycology at the National Institutes of Health.

“I think a lot of the [manufacturers] would have trouble getting a vaccine to market because of the demand and usage,” Perdue said during a live-streamed tick-borne disease panel discussion in June. “I think for one to really take off, it would have to be multipathogen or tick-focused.”

In other words, patients would be more willing and eager to receive one shot that prevents multiple tick-borne diseases, or all tick bites, rather than five or six different shots for each of the diseases that are present in the region where they live.

Lyme is the exception, he said, since the disease has become so common.

Tick-borne diseases now account for 95 percent of vector-borne diseases in the nation. Lyme disease alone accounts for almost three quarters of all reported vector-borne disease.

In mid-July, Pfizer announced that all of the more than 9,000 people participating in the trials of its VLA15 vaccine had completed their first three doses, an important step in the study.

The Phase 3 study has been underway for almost two years and is expected to be completed by the end of 2025. If the trial is successful, then Pfizer, along with its partner Valneva, a vaccine manufacturer, will apply to the US Food and Drug Administration in 2026 for permission to introduce the vaccine to the market.

Timing would then be “in the hands of the regulator,” wrote Kit Longley, a spokesperson for Pfizer, in a statement.

It wouldn’t be the first time a Lyme disease vaccine went to market; two decades ago, regulators approved a vaccine called LYMErix, but the manufacturer discontinued it due to poor sales. Some patients also claimed that the vaccine, pulled from the shelves in 2002, caused side effects.

The Pfizer vaccine, though, would come into a much different market, one with higher rates of Lyme. Some estimates suggest that almost a half a million people in the United States are diagnosed with and treated for Lyme disease every year.

Another preventative drug is being developed by the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School’s MassBiologics. The treatment would probably consist of a single shot for seasonal protection. Phase 1 human trials showing safety are complete, according to Sarah Willey, a spokesperson for the UMass Chan Medical School.

Phase 2 clinical trials have not yet started, Willey said.

Meanwhile, researchers are investigating a host of other ideas to prevent tick-borne illness, among them medication to prevent tick bites. In February, California-based company Tarsus announced a successful Phase 2 human trial for a tick-killing medication.

The tablet, which is very similar to the medication used to prevent tick bites in dogs, could be used a day before a person is outdoors in a region that’s infested with ticks. The drug would paralyze and kill the tick when it bites and, according to the Phase 2 trial results, would be effective for at least a month.

The people who participated in the trial allowed sterilized and noninfected ticks to bite them.

“Within 24 hours of biting, the tick would basically die and fall off, and that’s what we saw at very high levels,” said Bobby Azamian, cofounder and CEO of Tarsus. “That gives the patient, in essence, the power to prevent [ticks] on demand and have lasting protection against Lyme and potentially other tick-borne diseases.”

The company is in discussions with the FDA to determine next steps and plan Phase 3 trials, he added.

In contrast to mosquitoes, there are very few effective methods available to public health officials to control the population of ticks.

Mosquito districts in Massachusetts and other states regularly spray for mosquitoes and work to prevent the accumulation of standing water where mosquitoes breed.

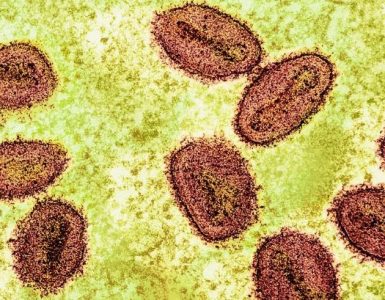

For ticks, though, those same efforts wouldn’t work. Ticks are an exceptionally difficult species to control. They feed in multiple life stages; huge proportions of their population carry a disease; and their key breeding habitat, deer, are literally moving targets. One tick can carry and pass on multiple infections in the same bite.

Ben Beard, principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of vector-borne diseases, said in a recent interview that he thinks a community-wide approach is necessary to have a hope of making a dent in the numbers.

For example, he said, a neighborhood could commit to moving playground equipment away from the woods and leaf litter; it could implement programs to reduce carrier rodent populations; spray insecticides in targeted areas; and train the people who lived there on personal protections. He pointed to homeowner associations and mosquito control districts as examples of organizing such efforts.

“I often think that something like that could be a useful way of combining all these different methodologies together,” he said.

Unfortunately, he said, mosquito districts have told federal health officials that they cannot afford to do tick control without increased funding.

Until there is a vaccine or more effective ways to reduce the population of ticks in New England, “the responsibility is falling on homeowners to protect themselves” by doing tick checks and wearing insect repellent, Beard said.

Source: Boston Globe