Every parent dreads it — holding the baby still while a nurse or technician pushes a needle into the tender flesh of a plump little thigh. The screams are bad enough — add the guilt at knowingly inflicting pain, even with the knowledge that a moment of discomfort is warding off death or weeks of illness.

Every parent dreads it — holding the baby still while a nurse or technician pushes a needle into the tender flesh of a plump little thigh. The screams are bad enough — add the guilt at knowingly inflicting pain, even with the knowledge that a moment of discomfort is warding off death or weeks of illness.

But what if there was another way? What if a little clear patch arrived by mail, one that could be stuck onto the child’s back and then would dissolve painlessly? Baby’s protected, no one cries and everyone is saved the time and expense of an office visit. Several labs are working to make it happen.

Not only would it ease distress, but Dr. Erin Giudice, a pediatrician at the University of Maryland, School of Medicine, thinks it might help fight a growing resistance to vaccination.

“Obviously, for little kids vaccination is very scary and we come at them with a big needle every time they need a vaccine,” Giudice said in a telephone interview.

“Having been around parents before and after their children receive multiple needle-based vaccines at the same time, I just can’t imagine that some proportion of why some families decide not to vaccinate … might have something to do with that we are giving some of these vaccines by a needle,” Giudice says.

Researchers for the government, for universities and at drug companies are all working to make this happen. Already a few needle-free alternatives exist — FluMist nasal spray, which vaccinates against flu with a squirt up the nose, is one. There are oral vaccines for cholera, typhoid and rotavirus.

The earliest vaccines were needle-free. Polio vaccine was once delivered orally — sometimes even on a sugar cube. And from ancient times, people inoculated one another against smallpox by scratching the skin and applying the scab from an infected person, or wiping a bit of cloth against a smallpox pustule and putting it into the nose. But these methods both only worked because they used a live virus – and they often infected people with the very disease they were meant to prevent.

New technologies may make it easier to design needle-free vaccines. One group got the go-ahead from the Food and Drug Administration last week to start testing a needle-free vaccine in people.

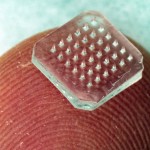

The Infectious Disease Research Institute (IDRI), a Seattle-based non-profit research group, has teamed up with a company called Medicago that works on vaccines using virus-like particles — little pieces of virus that can’t cause disease but that stimulate the immune system the way a live virus could. It’s delivered via a device made by Israeli company NanoPass using what are called micro-needles.

Dr. Steven Reed, founder and president of IDRI, says it doesn’t hurt and he thinks it will work better than standard, needle-delivered vaccines. He tried it himself.

“You just feel a little pressure — nothing else,” Reed says. The tiny device is covered with sharp little blades that scratch the skin. “It is incredibly small. You can’t even see it.” Reed says. It penetrates the first layer of skin, delivering the vaccine formula itself to immune cells called dendritic cells, which then pass it around the whole body to stimulate protection.

It’s delivered with a needle-free syringe, and Reed believes it would be easy for people to administer it themselves – much like people with diabetes can inject themselves with insulin.

IDRI’s vaccine is designed to protect against H5N1 avian influenza — the so-called bird flu that’s been cooking in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Middle East since 2003 and that many scientists fear could mutate to cause a deadly pandemic in people.

Besides being painless and perhaps something that could be mailed to people, the vaccine should eventually be cheaper and easier to make than current flu vaccines, which must be incubated in eggs and take months to produce. “Our main motivation, frankly, was to get superior efficacy by targeting the dendritic cells,” Reed says. It’s grown in tobacco plants and uses a booster called an adjuvant, which makes a little vaccine go a long way.

“Our idea is to ultimately produce a one-dose vaccine that you could give yourself – imagine a flu vaccine that you can easily administer using a simple, painless micro-needle device arriving in your mailbox,” said IDRI’s Darrick Carter.

A similar approach has been developed at Georgia Tech, but it does away with the syringe. The micro-needles are embedded in a patch that can be stuck on the skin until it dissolves. It’s being tested against flu and polio.

“The early studies they have that are published give us an indication that it might result in a better response in a shorter amount of time than some of the current vaccines,” says Martin Crumrine, a biodefense specialist at the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, which is paying for many of the studies.

In the case of a swiftly moving pandemic or a biological attack, that could be very important. It took months to make and roll out vaccine against H1N1 swine flu when it first broke out in 2009 and thousands of people died during the delay. While in the end H1N1 did not kill more people than annual seasonal flu does, the victims tended to be children and young adults rather than the elderly who are the most likely to die from flu.

NIH is also checking out an oral vaccine against anthrax. Made by PaxVax Inc. of San Diego, it’s given in a capsule – something that, if it works, would be a big improvement on the five injections that military personnel must now get to protect them against anthrax. Anthrax is considered one of the most likely biological weapons – it killed five people in 2001 when someone sent anthrax-laced letters to Congress and media companies.

Needle-free formulations may not only make patients happier, but they may be more stable and thus cheaper and easier to deliver. Most current vaccines must be refrigerated – a real problem for agencies trying to ship them, especially in hot regions and the developing world. “It’s much easier to give a tablet or two than it is to assemble people to give them injections,” says Crumrine.

Not all would be painless. “We are looking at a dengue fever vaccine that can be delivered using a device that you put on the skin surface, press a button, and it uses a small compressed air charge to put the vaccine into the skin,” Crumrine said. Does it hurt? “Probably,” he said.

A more experimental approach would use an electrical charge to make DNA from a virus or bacteria go right through the skin. Called electroporation, it’s being tested against West Nile virus, among other infections, Crumrine says.

NIH scientists are also working on a nasal vaccine, akin to FluMist, that can protect babies against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Using a nasal spray can stimulate immune cells right in the sinuses, throat, and lungs as well as throughout the body. RSV infects nearly every child by age, puts as many as 120,000 U.S. children into the hospital every year and globally, it kills 160,000 young children a year.

Other approaches in the works include a dry powder influenza vaccine being developed by Nanotherapeutics that can be inhaled to protect against a very common stomach bug called norovirus. It’s grown in tobacco plants, like IDRI’s flu vaccine.

Why is it taking so long? Vaccines are usually given to healthy people and so they must be much safer than drugs used to treat diseases. They’re also tricky to make — a small Maryland company called Iomai spent years testing a vaccine administered using a sandpaper-like device, only to have it fail at the last stages of testing last year. The parent company in Austria shut down most of the operation.

But Giudice would welcome any new approach that got more children immunized. “People are no longer taking it at face value that, yes, I should vaccinate my children,” she says.

“All the evidence we have that is backed up by science shows that it is way, way safer to vaccinate your children than not to vaccinate your children. I feel that anything we can do to make it easier for these parents is helpful.”

Source: NBC News