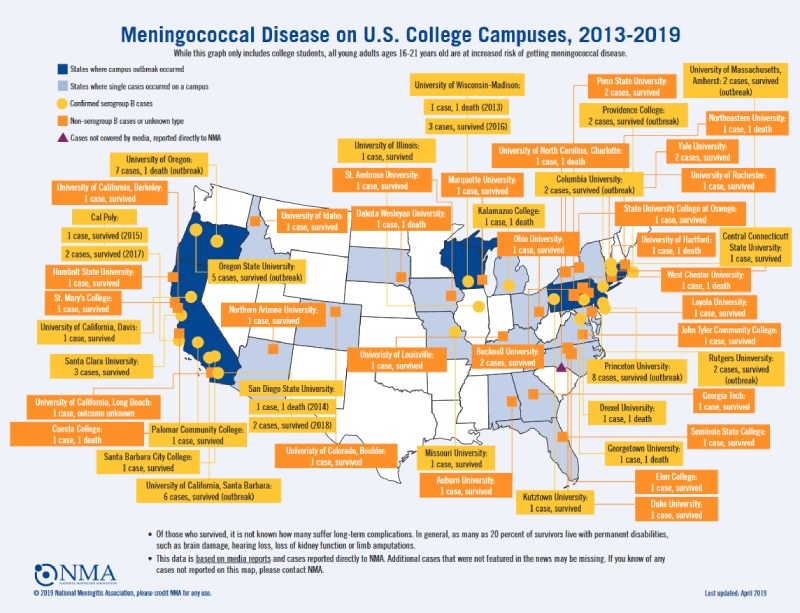

The CDC issued a health warning on April 9, 2022 about an outbreak of meningococcal disease in Florida. Multiple meningococcal disease cases in college students had been reported in the state of Florida over the last few months. On April 2, The Florida Department of Health announced three cases of bacterial meningitis in Leon County, Florida. All three young adults were confirmed to be current Florida State University students. Florida’s Department of Health (FDOH) published on April 7, 2022, that the number of cases identified so far in 2022 surpasses the five-year average in the state.

Meningococcal meningitis is a rare but serious disease caused by Neisseria meningitidis. The only known reservoir of the gram-negative bacterium is the human nasopharyngeal tract. Bacterial colonization is comparatively common, while the organism does not typically cause disease. New acquisition is a major risk factor for meningococcal disease, while long-term carriage is not. Under largely unknown circumstances, N. meningitis can penetrate the mucosa, invade the bloodstream, and cause invasive meningococcal disease (IMD), most frequently meningitis or septicemia. Rapid progression from first symptoms to death may occur within a few hours only due to the activation of the clotting cascade. The case fatality rate is 5%–10%, and even higher in places with low suspicion or with no access to ICU-type medical care. As many as 20% of survivors can experience significant, long-term sequelae, including limb loss or hearing loss. The bacterium is spread through contact with saliva or nasal secretions of a colonized person — whether through coughing, sneezing, sharing food or drink or kissing. It also can spread when an infected person is in a crowded space with poor ventilation for a prolonged period. From a public health perspective, one case must be considered to be an “outbreak” and all contacts need to be traced for prophylactic treatment.

Outbreaks have increased on college campuses over the last years. In a study published in BMJ, carriage rates for meningococci increased rapidly in the first week of term from 6.9% on day 1, to 11.2% on day 2, to 19.0% on day 3, and to 23.1% on day 4. The average carriage rate during the first week of term in October among students living in catered halls was 13.9%. By November this had risen to 31.0% and in December it had reached 34.2%. Independent associations for acquisition of meningococci in the autumn term were frequency of visits to a hall bar (5–7 visits: odds ratio 2.7, 95% confidence interval 1.5 to 4.8), active smoking (1.6, 1.0 to 2.6), being male (1.6, 1.2 to 2.2), visits to night clubs (1.3, 1.0 to 1.6), and intimate kissing (1.4, 1.0 to 1.8). Lower rates of acquisition were found in female only halls (0.5, 0.3 to 0.9).

Based on capsular polysaccharides, twelve meningococcal serogroups are recognized, of which six (A, B, C, W, X and Y) are responsible for nearly all cases of IMD. Capsular polysaccharide “B” is a self-antigen and therefore cannot be used for vaccine prevention. Two meningococcal “B” vaccines are, however, available using subcapsular (recombinant) protein antigens, one also including outer membrane vesicles (OMV). In the end, today there are 3 basic types of meningococcal vaccines:

- “Pure” polysaccharide vaccines

- Conjugate vaccines (against serotypes A, C, W, Y)

- Subcapsular meningococcal “B” recombinant protein vaccines

Vaccines can help control meningitis epidemics. The CDC recommends therefore routine administration of a MenACWY vaccine for all preteens and teens at 11–12 years of age with a booster dose at 16 years. In addition, the CDC recommends a MenB vaccine series for young adults 16–23 years especially for subgroups such as people in the military services or students in dormitories. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) further recommends both vaccines for persons with a very high risk for IMD, specifically those with persistent complement deficiencies, including persons taking eculizumab or ravulizumab-cwvz, persons with sickle cell disease or asplenia, HIV, and persons traveling to highly endemic areas including “Africa’s meningitis belt”.

Currently, ACIP recommends administration of a single MenB booster dose during an outbreak, when more than 1 year has elapsed since completion of the primary series. Uptake of meningococcal B vaccines remains low in the USA with 21.8% of 17-year-olds having received at least one dose in 2019, in contrast to 88.9% of 13–17-year-olds who received a MenACWY-conjugate vaccine. Therefore, while declines in serogroup C and Y disease have been observed in the US, serogroup B persists and is now the most common cause of outbreaks of IMD.

By Dr. Simone Müschenborn-Koglin Contributing Editor, GHP