In 2013, nearly 200 cases of measles came from people who traveled abroad

In 2013, nearly 200 cases of measles came from people who traveled abroad

Although cases of measles were virtually eliminated through 2011, people who travel abroad have brought the infection home have caused a recent spike in 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Thursday.

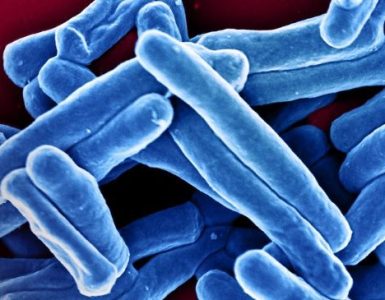

The measles virus is an infection of the respiratory system, typically characterized by high fevers and rashes, and is extremely contagious. That’s why scientists developed a vaccine 50 years ago that has helped prevent 10 million deaths, according to the CDC. And through 2011, the virus had been deemed eliminated in the U.S., meaning there was an absence of continuous disease transmission for more than 12 months.

But in 2013, some communities throughout the country saw a spike in reported cases. The CDC has recorded 175 cases, all of which were linked to individuals who brought the infection to the United States after traveling in another country.

“A measles outbreak anywhere is a risk everywhere,” said CDC Director Tom Freiden, in a statement. “The steady arrival of measles in the United States is a constant reminder that deadly diseases are testing our health security every day. Someday, it won’t be only measles at the international arrival gate so detecting diseases before they arrive is a wise investment in U.S. health security.”

On Sept. 13, the CDC released a report claiming the surge in cases was the largest outbreak of measles in 17 years. At the time the report was released, a total of 159 cases had been reported and the CDC estimated the number could exceed 220 cases by the end of the year.

In an editorial published Thursday in JAMA Pediatrics, physician Mark Grabowsky said the “greatest threat” to the country’s vaccination program comes from parents’ hesitancy to vaccinate their children. Grabowsky works in the Office of the U.N. Secretary General’s Special Envoy for Financing the Health Millennium Development Goals and for Malaria in New York.

“Although this so-called vaccine hesitancy has not become as widespread in the United States as it appears to have become in Europe, it is increasing,” Grabowsky writes.

But an even greater risk than parents refusing to vaccinate their children could come from parents who simply delay vaccination, according to Grabowsky, “because a delayed vaccination may add more person-years of susceptibility than that due to refusing vaccination.”

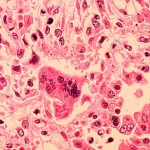

Currently, 430 children worldwide die from measles daily. But before the measles vaccine was approved in 1963, nearly every child in the United States became infected by measles, the CDC said, and 450 to 500 people died of the infection each year. Another 48,000 were hospitalized each year; 7,000 had seizures; and about 1,000 experienced permanent brain damage or deafness.

Still, the United States is the most populous country to have a recorded elimination of measles, according to a report published in JAMA Pediatrics Thursday. Additionally, the researchers found cases of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) had also been eliminated in the United States, through 2011.

Rubella is a more mild infection similar to the measles, and CRS can occur in a child before birth, if the mother contracted rubella during her first trimester.

According to the researchers, instances of all three infections remained low throughout the early 2000s. Reported measles cases remained below one case per 1 million since 2001; rubella cases remained below one case per 10 million since 2004; and CRS cases remained below one case per 5 million births.

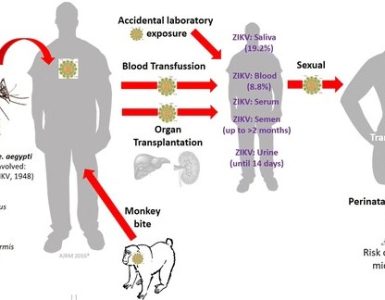

“However, because measles and rubella remain endemic in many parts of the world, importations will continue to occur,” the report said.

Before 1990, most imported cases of measles to the United States came from Mexico, but in 2013, half of all the imported cases came from Europe, according to the CDC.

“With patterns of global travel and trade, disease can spread nearly anywhere within 24 hours,” Freiden said in a statement. “That’s why the ability to detect, fight and prevent these diseases must be developed and strengthened overseas and not just here in the United States.”

Source: US News