Although climate change is often in the headlines, the potential for consequential shifts in infectious diseases that could result receives scant attention. As plants, animals and microbes continuously adjust to ecological stresses, there is a corresponding increased risk for the emergence of novel infectious diseases that should rightfully be among our primary concerns.

Although climate change is often in the headlines, the potential for consequential shifts in infectious diseases that could result receives scant attention. As plants, animals and microbes continuously adjust to ecological stresses, there is a corresponding increased risk for the emergence of novel infectious diseases that should rightfully be among our primary concerns.

Certainly, the exact extent of man’s influence on the extent or rate of climate change may remain controversial. However, there is an alternate form of direct human intervention on a planetary scale that is unequivocal and equally significant.

This is the rapidly growing illegal trade in exotic wildlife as either pets, consumption as food, imagined medicinal purposes, ivory for ornaments or skins for decoration. Much of this illicit commerce intentionally concentrates on endangered or nearly extinct species. Want to own a baby tiger? It can be shipped with ease. In fact, according to the World Wildlife Fund, there are more tigers in American back yards than there are in the wild.

The extent of this illicit worldwide trade is vast but is not widely known. It may be in the shadows but it is at least the fourth largest global illegal industry following drugs, human trafficking, and illegal arms. The revenue stream of this illegal traffic amounts to tens of billions of dollars annually. Demand is voracious and the prices can be astronomical.

A gorilla can be yours for $400,000. A baby giraffe is a relative bargain, only $60,000. Birds, mammals such as monkeys, lizards or other reptiles, snakes and insects are all commonly traded. The market for uncommon and endangered species is particularly brisk. The prices are higher for nearly extinct species as they are the most prized for bragging rights in this perverse marketplace.

The abusive treatment of these animals subject to this trade is heart-rending.They are confined to small cages and subjected to unnatural and cruel conditions. Mortality is high during transport and their target owners are ill-equipped to provide adequate care. However, even as terrible as these abuses are, there is a further facet of this activity that is little discussed but of paramount importance. There are a large variety of infectious diseases that can be inadvertently spread through this illegal trade that can put entire populations of animals including us humans at significant risk.

The vast majority of the deadliest infectious diseases that have afflicted mankind throughout our history are termed zoonotic infections. These are infections that are spread from animal to man or indeed, man to animal. Zoonotic disease also accounts for most emerging infections, estimated at over 60% of such deadly novel infectious diseases.

Of these, the great majority (70%) originate in wildlife. For example, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is now believed to have originated in bats, was spread to civets (small cat-like nocturnal mammals native to tropical Asian and Africa and coveted in the illegal wildlife trade) and then jumped to humans. The 2003 SARS epidemic in China and Hong Kong infected over 8,000 people and was associated with more than 700 deaths. Other terrifying disease have similarly emerged. Ebola virus has been spread by the importation of primates from the Philippines but fortunately remained restricted to monkeys.

Aside from SARS, other recent zoonotic diseases include Ebola, HIV, and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

Many infections such as these can also spread to man through intermediary insect vectors. For example, the European bubonic plague was spread by fleas on rats that came with trading ships arriving from distant ports during the Middle Ages. In that epidemic (1348-1350), it is estimated that 50% of the European population was killed. The entire fabric of civilization was destroyed for generations.

It may be hard to imagine that such events could ever be repeated in our modern context with available antibiotics and vaccines, but the fact that no recent crucial emerging infectious disease has similarly spread is simply a matter of good fortune rather than intelligent policy.

Clearly, every effort needs to be made to attempt to interdict this highly dangerous trade. Importantly too, a similar set of concerns applies to the abundant legal worldwide trade of domesticated and non-domesticated animals. Their importation often forces high density surroundings that include an unnatural collection of species.

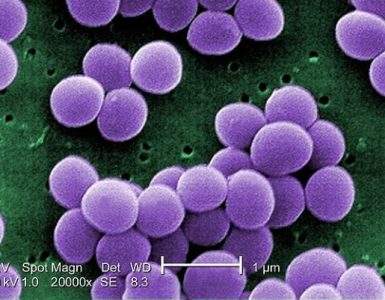

This is a potent environment for the cross-species transmission of atypical pathogens. In such circumstances, the risks are great and the results are completely unpredictable. It is known that the majority of emerging infectious diseases are spread by drug-resistant pathogens and these circumstances are its breeding ground.

It is disturbing that there are few global resources directed towards disease prevention and emergence. Of the little available that is available, much is poorly allocated. Obviously, there is no disease surveillance program in the illegal wildlife trade, but even for legally imported animals, there is little oversight.

Quarantine is required for only a few animal species. Mandatory testing of these imported animals exists for some diseases but ignores other consequential ones. Even worse, this testing is often left in the hands of the importer rather than being conducted by an objective agency. Therefore, a critical focus on the illegal wildlife trade must be matched by a thorough re-examination our procedures and policies regarding legal animal importation.

At this moment, good luck has permitted complacency. However, the lack of a disastrous outcome to date does not mitigate the actual risks. It is an absolute certainty that there will be a next global pandemic since these occurrences are a part of our basic planetary biological system from the inception of life forward.

The only operative questions are these: when, where, and under what circumstances will it materialize? Clearly, our best defense is to diminish the risk and mitigate the effects of that inevitable outcome prior to its emergence through scientifically grounded policies and rigorous procedures.

Source: RDE – Rare Disease Report