When the clocks struck midnight in New Delhi on 12 January, India marked the first year in history it has recorded no new cases of polio.

This is a huge milestone for a country many experts thought would be the last place on earth to get rid of the crippling virus. It is also an exciting step forward for global health workers battling to make polio only the second human infectious disease after smallpox to be eradicated.

“If all the data comes in clear over the next few weeks, then India, for the first time, will show up as an unshaded area on WHO polio maps,” said Sona Bari of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Global Polio Eradication Initiative. “This is a great start to the year for India.”

While India celebrates, global health authorities are debating how to reduce the risk that vaccines containing live viruses may reintroduce the disease to places only just becoming polio-free. It’s a tricky judgment of timing, risk and cost, but the fact it’s being discussed is a sign of how far the polio fight has come.

India’s success leaves just three countries — Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria — where polio is still endemic, and sets an example for what could be in store for them.

“It shows we’re going to get it done elsewhere,” said John Hewko, Chief Executive of the charity Rotary International, which has spearheaded the global polio fight for three decades.

Bill Gates, whose philanthropic foundation has also been key to the fight, said it showed the disease can be halted “when countries combine the right elements – political will, quality immunisation campaigns, and an entire nation’s determination”.

Since the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was launched in 1988, worldwide polio cases have fallen by 99 percent. Back then the disease was endemic in 125 countries and caused paralysis in nearly 1,000 children every day. By contrast, in the whole of 2011, there were only 620 new cases worldwide

Experts are under no illusion that getting the three remaining endemic countries to India’s zero level is a challenge that will not be overcome for several more years. But as the prospect of global eradication comes into sight, it brings a new dilemma that will be a focus of the WHO’s Executive Board next week.

Live of Inactivated?

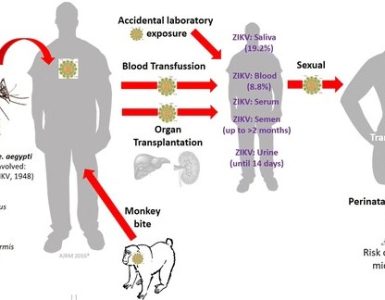

At the heart of the issue are oral polio vaccines, which are highly effective and owe much of their success to the fact they are cheap, easy to deliver and contain live polio virus strains. Because type 2 has already been eliminated, a three-strain oral vaccine called tOPV is being phased out in favour of a bivalent or two-strain one called bOPV which fights type 1 and type 3. The problem remains that the viruses are live.

“Looking to the future we clearly want to get away from using oral polio vaccine (OPV) altogether – because with OPV we continue to be putting live viruses into people and into the environment,” said David Salisbury, Chair of the WHO’s European Certification Commission for Polio Eradication and Britain’s director of immunization.

Bari described it as a tipping point. “When the risks from the vaccine start to outweigh the risks from the wild virus, that’s when we should make the decision,” she said.

There is an alternative called inactivated polio vaccine or IPV, but unlike OPV it’s expensive to make and difficult to deliver because it has to be injected by trained health workers in clinics.

Most wealthy countries, like the US and UK, dealt with the issue by using oral polio vaccines to stop transmission and maintain that halt, then switching to inactivated polio vaccines when they were sure they had the virus beaten, Bari said. For poorer countries with limited health services, infrastructure and resources, that won’t be so easy, so research teams are looking at ways of trying to make IPV more accessible.

One option is to lower the amount of antigen needed in the vaccine by adding an adjuvant, or booster, that would be cheaper. Another might be developing a way of injecting only into the skin, rather than under it, a method that would require a lower – and therefore cheaper – IPV dose.

Immediate Task

Salisbury stressed the decision to switch the vaccine is something for the future, and halting polio transmission worldwide is still the most pressing task. “These will be very difficult judgments but we’ve got to start discussing them now. If we didn’t we’d be criticised in future for not having thought things through,” he said.

India’s success came only after a massive, $2 billion battle mostly financed domestically. WHO Director General Margaret Chan described it as “arguably its greatest public health achievement.” In the last year alone, there were two separate nationwide immunization programmes, each of which immunised 172 million children under the age of five over five days.

To reach people on the move, mobile vaccination teams were sent out immunize children at railway stations, on trains, and at bus stands, market places and construction sites.

The country’s lone case last calendar year was on 13 January in a two-year-old girl in Howrah, close to Kolkata in West Bengal.

“The evidence from India is if you do the job well, you stop polio,” Salisbury said. “If it can be done in India, technically it can be done anywhere.”

Source: AlertNet