Only the female of the species of infection-spreading mosquitoes is a threat to humans – the males do not need to provide for developing eggs by biting us for blood. Our practical exploitation of this fact in a fight against tropical diseases could now be possible following scientists’ discovery of a genetic switch that determines sex in the yellow fever mosquito.

Only the female of the species of infection-spreading mosquitoes is a threat to humans – the males do not need to provide for developing eggs by biting us for blood. Our practical exploitation of this fact in a fight against tropical diseases could now be possible following scientists’ discovery of a genetic switch that determines sex in the yellow fever mosquito.

The findings, published in Science Express, are from researchers with the Fralin Life Science Institute at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.

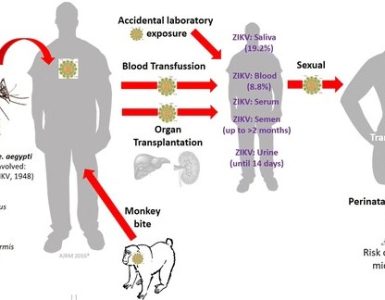

A gene was found to be responsible for sex determination in Aedes aegypti, or yellow fevermosquitoes – the invasive species that can transmit dengue and chikungunya as well as yellow fever viruses.

After injection of the gene into mosquito embryos, over two thirds of the female mosquitoes developed male genitals and testes, and after a genetic manipulation technique in male mosquitoes, they developed female genitals.

The authors conclude: “This study provides the foundation for developing mosquito control strategies by converting females into harmless males or selectively eliminating deadly females.”

One of the authors, Prof. Zhijian Jake Tu, a biochemist at Virginia Tech, is enthusiastic about an avenue of research opened up by characterizing the gene, which the team has dubbed “Nix”:

“Nix provides us with exciting opportunities to harness mosquito sex in the fight against infectious diseases because maleness is the ultimate disease-refractory trait.”

Another of the authors, Brantley Hall, a doctoral candidate in Prof. Tu’s laboratory, adds: “Targeted reduction of A. aegypti populations in areas where they are non-native could have little environmental impact, and drastically improve human health.”

The Nix gene is located on the equivalent of the Y-chromosome in the insects, the journal report explains – within a male-determining region, or the “M locus.”

Scientists have difficulties in identifying genes in regions of the genetic code such as this because of their highly repetitive nature, and until now, in spite of the availability of genomic resources, “no M factor has yet been characterized in any insect.”

The researchers hunted down the mosquito’s M-linked genomic sequences and found and named the Nix gene. Because it had a “tantalizing link to sex determination,” they then tested this theory with genetic experiments.

Manipulation of the gene caused malformation of mosquito genitalia

By manipulating the gene’s expression, they discovered that it was “both required and sufficient to initiate” male development, and that changes to the M factor in A. aegypti resulted in the sex organs of the mosquito being deformed:

- Switching off the gene completely resulted in many males losing important features of their genitalia

- Expressing the gene on different parts of the mosquito’s genetic code masculinized the sex organs of many females.

Zach Adelman, entomologist and associate professor at Fralin, says: “We’re not there yet, but the ultimate goal is to be able to establish transgenic lines that express Nix in genetic females to convert them to harmless males.”

The biologists say the A. aegypti mosquito began to spread from Africa in the 1700s, travelling by ship. Among a small fraction of mosquito species that carry and transmit pathogens to humans, it is highly adapted to our environments.

Some practical tips to control the dengue-transmitting yellow fever mosquito are found in a CDC factsheet. Because they use water containers to lay their eggs, example advice is to check the yard weekly for water-filled containers, throw away any not needed, cover others, and so on.

Source: MNT – Medical News Today