Not so far in the future, the medical complications linked to obesity – an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes, heart attack, stroke, cancer and end-stage liver disease – could be reduced by a simple vaccine.

Not so far in the future, the medical complications linked to obesity – an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes, heart attack, stroke, cancer and end-stage liver disease – could be reduced by a simple vaccine.

People who got the vaccine would still be overweight, but the strain on their organs and organ systems would be greatly diminished, allowing doctors to better treat the obesity itself.

Scientists at the Methodist Diabetes and Metabolism Institute hope to create this vaccine within the next decade, based on their groundbreaking research surrounding fat cells.

“We always want to emphasize that the best treatment for obesity is diet and exercise,” said Tuo Deng, first author on the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the institute.

But a vaccine that reduces or disrupts the production of inflamed fat cells could “revolutionize” the treatment of obesity’s worst consequences, he added.

Along with Christopher J. Lyon, a senior research associate at the institute, and Willa A. Hsueh, the institute’s director, Deng led a team that studied fat cells in obese women and overfed male mice. The surprising results were published as the cover story in the medical journal Cell Metabolism on March 5.

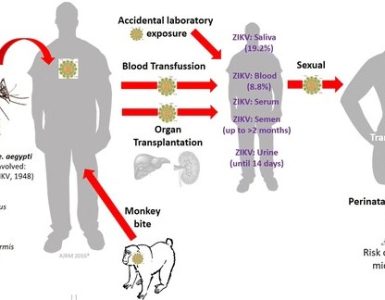

The scientists found that high-calorie diets cause fat cells to send out false distress signals through certain proteins. Usually, these proteins indicate that the fat cells are fighting off bacteria and viruses, although that isn’t the case in this scenario.

Nonetheless, immune cells in the body are tricked into believing there’s cause for alarm and go haywire, becoming inflamed. Inflammation of fat tissue contributes to the development of Type 2 diabetes and other diseases.

The surprising discovery here is that the fat cells instigate the inflammation; for a long time, fat cells were thought to do little more than store and release energy.

The team even commissioned a cartoon image to help explain the process they uncovered, featuring a fat cell and an immune cell in a boxing ring. The fat cell has thrown a punch and the immune cell’s boxing gloves have burst into flames.

Although the scientists have identified the group of proteins that trigger the inflammation as major histocompatibility complex II, or MHCII, they’re still trying to identify the specific substance – or antigen – that activates the inflammation in the immune cells.

Once they find it, they can design the vaccine.

“We don’t have a vaccine yet,” Lyon explained. “The vaccine would suppress the response to the antigen and decrease the overall level of inflammation in the tissue.”

To find the best candidates for the vaccine, doctors would determine the body mass index of their patients – anyone with a BMI greater than 30 is considered obese – do blood tests and take biopsies of their fat tissue, Hsueh explained.

“I would prefer that people get the vaccine early,” she said.

Waiting just puts more strain on an already strained body, she added.

“Even now, teens are having heart attacks from diabetes,” Lyon said.

Hsueh and her department are grateful to Mauro Ferrari, CEO of the Methodist Hospital Research Institute, for funding their ongoing research.

And Hsueh is quick to note that a significant benefit of the vaccine would be financial:

“It’s the complications related to obesity that cost all the money,” she said.

Source: Chron