The source of a deadly outbreak of Escherichia coli bacteria in Germany remains elusive

as German officials today announced that the first tests of samples from a sprouts farm implicated in the outbreak were negative.The German farm had been shut down yesterday by authorities and the region’s health minister had advised people not to eat the vegetables. The confusing turn of events comes less than a week after German officials suggested Spanish cucumbers were the source, only to later backtrack.

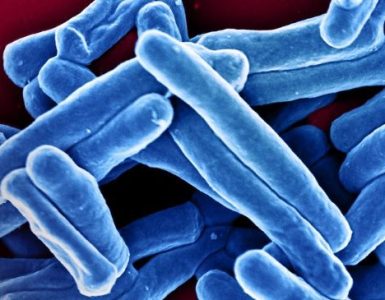

Researchers are now analyzing the genome of the bacterium to understand its evolutionary history and possibly identify its source. Closer analysis of the genome might also offer some clues to how the Shiga toxin made by the bacterium is attacking the brain. This toxin normally targets the kidney, triggering the often fatal development of hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). Usually neurological symptoms are seen in only a few percent of HUS cases, but in the current outbreak “about half the patients with HUS are developing neurological symptoms,” Christian Gerloff, head of the neurology department at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, told ScienceInsider today.

Alarm bells started going off when some patients showed problems finding words or giving the date, Gerloff recalls. It quickly became clear that a lot of patients were developing problems reading or doing simple calculations. “Patients were mixing up words and were disoriented. Later they developed muscle twitching and then progressing to epileptic fits,” Gerloff says.

At the clinic in Hamburg, a team of neurologists now screens all HUS patients once a day to look for any unusual signs and treats any patients with neurological symptoms with anticonvulsants to prevent epileptic fits. But the most surprising thing to Gerloff was that the bacteria does not appear to cause strokes. “That is what we were expecting mostly,” Gerloff says. But patients with neurological symptoms showed no signs of structural brain damage when examined with magnetic resonance imaging. “It is usually assumed that the Shiga toxin binds to the endothelium and leads to swelling and clotting, obstructing the vessels,” Gerloff says. “So why are we not seeing any strokes?” Autopsies of two patients could lead to new insights in the next few days, the neurologist says. But for the time being, it is just one more perplexing detail of a pathogen that has sprung quite a few surprises already.

Source: Science/AAAS