After 31 years of research, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has filed for regulatory approval for the first-ever malaria vaccine–which also happens to be the first vaccine developed against a parasite. The clinical trial results of the vaccine, called RTS,S, have been encouraging.

After 31 years of research, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) has filed for regulatory approval for the first-ever malaria vaccine–which also happens to be the first vaccine developed against a parasite. The clinical trial results of the vaccine, called RTS,S, have been encouraging.

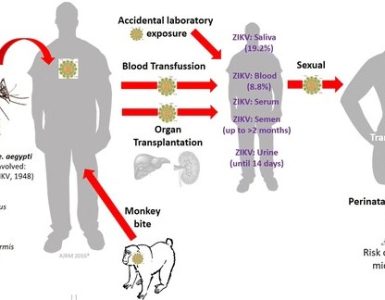

Malaria is an insidious and preventable disease, killing almost one child per minute. In high-risk areas, there’s more than one case per 1,000 people. Depending on who you talk to, insecticide-treated bednets prevent anywhere between 5% to 50% of cases, and efficacy is largely dependent on how consistently people use them. A vaccine–which requires no effort in patients beyond getting the initial shot–used in combination with bednets could prevent even more cases of the disease.

GSK’s journey towards a malaria vaccine began with an idea: to take a small piece of the major protein that forms the surface of the parasite and make a vaccine against it. After 10 years of experiments, researchers made little progress using the method. But the failure of the effort coincided with advances in modern immunology indicating that T-cells could have a hand in protecting against malaria. “At that time, we changed our strategy to make a vaccine [using]antibodies and T-cell immunity,” says Moncef Slaoui, chairman of global R&D and vaccines at GSK.

When a mosquito bites, it injects between 10 and 100 parasites into the bloodstream. The first parasite takes 30 seconds to two minutes to find its way into the liver and hide there, before bursting out five days later and infecting blood cells. That’s when people get sick. Antibodies (the initial method GSK tried) could only kill the parasites during their short period inside the bloodstream, while T-cell immunity can kill parasites where they’re hiding. Combined, the two methods are reasonably effective.

After 18 years, from proof of concept to clinical studies, we now know how powerful the RTS,S vaccine could be. In trials, the vaccine showed 46% protection in toddlers (5 months to 17 months old) and 27% protection in infants (6 weeks to 12 weeks old).

For context: that’s prevention of 1,000 cases per 1,000 toddlers over a year and a half (many kids have more than one case per year) and 500 cases prevented per 1,000 infants over the same time period. But given its partial efficacy, it’s probably not the holy grail to end malaria. “There’s still room for improvement,” admits Slaoui.

If it is approved, the vaccine could be available in a year. GSK is selling it with a 5% markup in cost, and proceeds will go towards future research. The company is already working on second-generation vaccines, in addition to an oral medicine that cures a type of malaria found in Asia and Latin America with just one dose.

Source: FastCompany – Co.EXIST