A vaccine against pneumococcal disease, which is a major killer of children in Africa, has cut the disease rate by more than half, new research has found.

A vaccine against pneumococcal disease, which is a major killer of children in Africa, has cut the disease rate by more than half, new research has found.

The study, involving Otago researcher Professor Philip Hill, monitored a population of 200,000 people in The Gambia, West Africa, before and after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

This vaccine was designed to combat a disease that takes a grim toll on under five year olds in particular.

The findings are published in the prestigious journal Lancet Infectious Diseases.

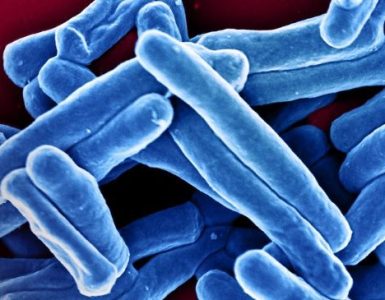

Professor Hill says pneumococcal bacteria cause pneumonia, blood poisoning and meningitis across the world.

“These new generation vaccines are designed specially to be effective in young children, although they have limitations. These include being only able to cover a certain number of the subtypes, known as serotypes, of the pneumococcus bacterium,” he says.

The fear was that other serotypes of pneumococcus would take their place, blunting vaccine impact.

In a huge seven-year surveillance project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the investigators assessed 15,000 patients presenting to hospital with specific symptoms to identify those with pneumococcal disease over seven years, making sure all criteria for investigation and all processes to identify cases of the disease were consistent over time.

Professor Hill says they found that the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) decreased by 55% in the 2–23 month age group, from 253 to 113 cases per 100000. This was due to an 82% reduction of serotypes covered by the vaccine. In the 2– 4 years age group IPD incidence decreased 56%, from 113 to 49 per 100,000, with a 68% reduction in vaccine serotypes.

The incidence of non-vaccine serotypes in children aged under five years increased 47% from 28 to 41 per 100,000, but not enough to stop the vaccine being highly effective.

“This important study has provided the evidence needed to support the ongoing roll out of these vaccines in low and middle-income countries—they can be confident that they will see substantial reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease,” he says.

Professor Hill says this outcome is especially pleasing from a number of points of view.

“First and foremost it is wonderful that the vaccine is having an impact in Africa, where the rates of pneumococcal disease are some of the highest in the world.”

“Second, it shows the quality of the work of the large team of people, who have been able to conduct surveillance for this disease under difficult circumstances with the precision that is required. And thirdly, for me personally, there is a great deal of satisfaction that a project myself and others started over eight years ago in The Gambia is producing the outcomes that were intended.”

“I feel greatly privileged to be part of this programme of work. It is exactly what I dreamed of being involved in as I went through my training in New Zealand. I have also been able to send three students from Otago so far to do research in the project, which is exciting.”

An editorial accompanying the Lancet Infectious Diseases paper described the study as having important implications for the introduction of PCVs in all African countries, where the rates of invasive pneumococcal disease remain around ten-fold higher than those in developed countries.

Professor Hill was the initial leader of this project, guiding its establishment. Dr Grant Mackenzie of the MRC labs in The Gambia has led the project since 2008.

Dr Mackenzie has led a team of more than 100 people and managed the more than $10M in funding from the Gates Foundation. Professor Hill has remained an investigator, visiting the project every year, with a specific focus on trying to identify any problems with the project that could compromise its quality.

Source: New Zealand Doctor Online