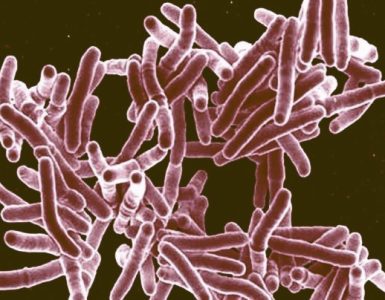

A virus is a moving target. And for 30 years, HIV has been constantly on the move making new copies of itself that are slightly different than before, ready to attack the immune system that the body needs to protect itself against a host of pathogens. For scientists looking for a vaccine for HIV/AIDS, it’s been a long search filled with disappointing failures.

A virus is a moving target. And for 30 years, HIV has been constantly on the move making new copies of itself that are slightly different than before, ready to attack the immune system that the body needs to protect itself against a host of pathogens. For scientists looking for a vaccine for HIV/AIDS, it’s been a long search filled with disappointing failures.

“There’s no vaccine and no cure. And we can have a debate about which will come first,” said pioneering AIDS researcher Mark Wainberg, director of the McGill University AIDS Centre, who has made significant contributions to the field since the beginning of AIDS when the virus was first isolated in 1983.

Wainberg’s team, in collaboration with drug company BioChem Pharma Inc., identified 3TC as an anti-viral drug in 1989, and he says he’s proud to be among the scientists who have helped turn the corner on HIV/AIDS.

The quest began in earnest when previously healthy young men with bluish-purple skin lesions, later identified as a rare form of cancer — Kaposi’s sarcoma — and other complications like pneumonia, began dying by the hundreds and thousands. A mystery disease was destroying their immune system.

Margaret Heckler, Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, famously predicted in a press conference in April 1984 that a vaccine will be ready for testing in about two years. Instead, rates of infection skyrocketed to epidemic proportions.

The development of antiretroviral drugs in 1996 revolutionized treatment of patients with AIDS. The drugs turned an automatic death sentence into a manageable chronic disease.

“And here we are, 30 years later, and we still don’t have a vaccine. There’s a lot of pessimism about the likelihood of a vaccine because the virus mutates all the time,” said Wainberg, whose lab at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital has spent years on vaccine development, among other therapies.

According to the World Health Organization almost 70 million people have been infected with HIV — about 35 million people have died of AIDS since the beginning of the epidemic, and in 2011, 34 million people were living with HIV.

“Hardly anyone dies anymore of AIDS. New drugs are coming out, and the progress has been fantastic,” said Wainberg, however that’s not the case in the developing world where access to high-quality drugs is limited.

Even though drug companies have agreements to license antiretroviral drugs on patents as generics, the therapies are not free and someone has to pay for them, he said. So the onus is on rich countries like Canada to chip in for global health. But that too has limits, and the only solution is a cure, Wainberg said, and in the meantime, the development of strategies that minimize infection risks.

But some experts think a vaccine is the best hope against AIDS. The U.S. National Institutes of Health said it will put $186 million over the next seven years to fund the Centers for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology & Immunogen Discovery in the quest for a new generation of vaccines that provoke protective antibodies against infection.

In Canada, Université de Montréal scientist Cécile Tremblay is the lead investigator of a major Canadian study for the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network looking at why a group of HIV infected people — roughly five per cent of the population — remain healthy and are slow to go on to develop AIDS.

What knowledge can be gleaned from their immune response to infection, demanded Tremblay, scientific director of the Quebec Public Health Laboratory.

“They seem to control their disease without treatment of antiretroviral drugs,” Tremblay added. “We’re studying them in terms of genetics and (their) virus, how their immune system works, to understand what they have that others don’t. We’re hoping it will give us clues as to how a vaccine could be more effective.”

Tremblay also heads a pilot project, a France-Canada collaboration, that aims to find out whether healthy people in very high-risk groups can prevent infection by taking anti-HIV drugs before sexual contact.

Key to a long life for someone with HIV/AIDS is the highly effective antiretroviral drugs that dramatically changed patients lives, but unfortunately 25 per cent of people don’t know they are infected and in developing countries, that rate jumps up to 80 per cent, Tremblay said, and so they don’t receive treatment.

“Until we refine strategies on testing and treatment, we need to do something for risk,” she said.

In Paris and in Montreal, researchers will be looking at whether the most widely used antiretroviral pill, trademarked Truvada, can offer protection against infection if taken on an “on demand” basis before sexual contact as pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Putting healthy people on this drug cocktail already showed a proof-of-concept in an American study, Tremblay said, but results were spotty. It was effective in people who stuck to the drug routine — about 45 per cent — and in this group protection jumped to 80 per cent.

“We thought of another scenario. We’re not asking them to take a pill every day. Instead of taking it continuously, they would take the drug as needed, say before going out on a Friday night and once a day until you’re done for the weekend,” Tremblay said. “Surprisingly, studies show that sexual activity can be predicted.”

The pilot project will recruit 100 people to the Montreal site initially — gay men who have sex with men, have a history of sex without condoms and with multiple partners. This is a placebo-controlled study and half the participants will be getting a sugar pill and the other half will be getting the drug.

Both groups will get counselling, safe-sex education and testing for sexually transmitted diseases every two months.

The U.S. study garnered controversy with some protesting that antiretroviral drugs are not readily available to all and therefore supplies should be prioritized for people who are sick rather than given to people who are not even infected.

“What we would love to see is an added benefit of using a pill for people who are at high risk. Then the way to implement that has to be discussed. Society has to decide where to put its money. Treat people who are HIV positive or treat those who are at risk,” Tremblay said.

That said, people get tired of taking pills, which is why education, prevention, treatment and new axes of research are so important, Tremblay said.

Wainberg’s team at McGill will be looking at Tremblay’s study for analysis of drug resistance, one of several new drugs approved in the last five years. That’s been a problem for all the drugs developed since the beginning of the epidemic, he explained. As the virus mutates and develops resistance to particular therapies, the drugs then become less effective.

Wainberg said his team is eyeing drugs in the pipeline (although nothing is certain yet, he added) that might be able to fight against their own obsolescence.

“Our approach is to study whether the virus is no longer able to multiply — not just because the drug works, but if the virus tries to develop resistance it ends up running out of steam,” he said. “The mutations that might enable HIV to become resistant might simultaneously be fatal to the virus itself.”

Governments have invested major funds in new research and top-notch scientists in Germany, France, the United States, Britain and Australia “are part of a critical mass of researchers all trying to find a way to cure HIV,” he said. “And hopefully someone will hit the jackpot.”

Tremblay said there’s hope now for a world free of AIDS.

“We’re now at the crossroads of the next generation, we can hope the next generation will be free of HIV — if, and that’s a big if — treatment is available to everyone who is affected, and the cycle of transmission is broken. We can do great things with the tools we have.”