Roll up your sleeves. Effective new vaccines have hit the market for everything from pneumonia to shingles to RSV to, of course, Covid-19. And that’s just the beginning.

There were 258 vaccines in development as of 2020, according to a report from trade group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA. It found that $406 billion in direct medical costs were saved due to routine childhood vaccination of U.S. children born from 1994 to 2018.

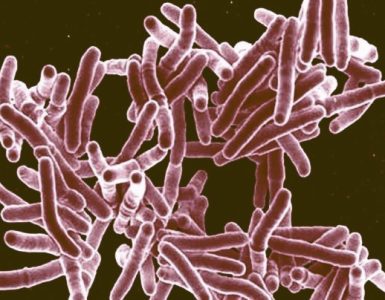

Pharmaceutical companies are currently developing everything from personalized cancer vaccines that could cost tens of thousands per patient to vaccines that prevent developing-world diseases like malaria or tuberculosis. Improved flu, pneumonia, and meningitis vaccines will also be available in your neighborhood pharmacy.

Scientists are testing vaccines to prevent a virus believed to cause multiple sclerosis in some people. Someday, vaccines could routinely treat acne, protect against peanut allergies, and even prevent heart disease or help treat Alzheimer’s disease.

Consider cancer, a hot spot in vaccine research, according to PhRMA. Preventive vaccines against hepatitis B and the HPV viruses, first approved in 1981 and 2006, respectively, have reduced rates of liver and cervical cancer.

Whereas vaccines have traditionally been used to prevent infectious diseases, scientists have begun researching therapeutic vaccines to treat people who are already sick, including cancer patients.

Last year, Moderna conducted a trial in which personalized vaccines that used genetic sequencing to target specific mutations in each patient’s cancer helped slash the recurrence rate for metastatic melanoma. The two pharmaceutical companies plan to try the same approach on lung cancer and other carcinomas.

“One of the most powerful things in human health is the immune system,” says Moderna President Stephen Hoge, himself a physician. “We now understand cancer as a disease that emerges later in life principally, not because of mutations but because the immune system gets less effective in controlling it.”

This wave of new vaccines is part of a sea change in medicine.

In the 1940s and 1950s, widespread adoption of antibiotics made dangerous infectious diseases such as strep throat or pneumonia easily treatable.

“In the 1950s, many vaccines had funding taken away from them because we were in the golden age of antibiotics, and they didn’t think we needed vaccines,” explains scientist Annaliesa Anderson, who leads vaccine research and development at Pfizer

At the same time, pharmaceutical companies began cranking out powerful drugs that lowered blood pressure, reduced blood sugar and cholesterol levels, prevented strokes, and treated hundreds of other ailments big and small for millions of Americans.

Some of those medicines have unwanted side effects, but companies still have a large number of drugs in the pipeline, which is unlikely to change. As for antibiotics, they have run into resistant bacteria that limit their effectiveness; a study carried out by the World Health Association and others found that more effective use of existing vaccines plus development of new vaccines could avert 500,000 deaths globally a year associated with resistance to antimicrobials (a broader category that includes antibiotics).

Vaccines, by contrast, use the body’s own immunological response to fight off disease. They tend to have fewer long-term side effects than drugs, despite the recent surge in vaccine hesitancy in the American public.

“Why are vaccines better than drugs? Vaccines prevent things from ever happening so you never have to treat them,” says Kawsar Talaat, an infectious disease physician and vaccine scientist at Johns Hopkins.

Pharmaceutical companies didn’t prioritize vaccines because they tend to be less profitable than medicines that must be taken every day for years, Talaat says. “It has changed quite a bit in the past few years.” Since Talaat completed her residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin in 2001, she says she has seen drops in patients with certain types of pneumonia, rotavirus, and shingles because of vaccines.

Drug companies are spending big on vaccine development. New technologies have made it possible for them to develop effective vaccines more quickly and cheaply than in the past. When the Covid pandemic hit, drug companies were able to deliver effective vaccines to the public in roughly a year—a fraction of the time that vaccines typically take. Pfizer and partner BioNTech (BNTX) and Moderna received tens of billions of dollars in revenue selling their Covid vaccines.

But the end of the pandemic also underscored the business challenge that vaccines pose for drug companies. Sales of Covid booster shots have cratered this year, and Moderna—whose Covid vaccine is its only approved product—is scrambling to get new products on the market. It hopes to have a respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, vaccine approved by the spring of 2024, followed by a flu vaccine, and then a combination Covid-flu-RSV shot in 2025.

“Our vision is to combine the viruses that drive flulike symptoms into a single dose so you don’t need to worry which virus you get the booster for, whether it’s Covid, RSV, or flu,” says Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel. He says that respiratory diseases are the No. 3 or No. 4 killer in most countries, and that a combo shot could prevent most of them.

Pfizer, meanwhile, is working on its own combination respiratory virus vaccine and is training its sights on infectious disease of all stripes. Anderson, the Pfizer vaccine R&D chief, points to the development of a vaccine for pregnant women for Group B strep bacteria. The bacteria isn’t usually dangerous for women but can be transmitted during birth and can lead to sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis, or seizures for babies. She says this strep is particularly problematic in less-developed countries and communities in the U.S. where pregnant woman get less prenatal screening.

GSK and Sanofi, leading vaccine makers in the U.S., are huge, diversified companies selling an array of products. They all see vaccine development as a key area of business over the coming years.

Sanofi, a leader in selling flu shots, has a stated goal of doubling vaccine sales and becoming the industry leader in immunology by 2030, hitting 10 billion euros ($10.84 billion) in annual vaccine sales. Sanofi says it will have three to five major vaccines in final-stage trials by 2025, including an RSV toddler vaccine, a pediatric pneumonia vaccine, and an improved yellow fever vaccine.

GSK sells the only shingles vaccine available in the U.S. It is improving its pneumonia vaccines so that they treat more strains and developing a therapeutic vaccine for HSV. Phil Dormitzer, GSK’s global head of vaccine R&D, notes that his company is doing early-stage research on a vaccine for gonorrhea, which is a growing health problem because of antibiotic-resistant strains of the venereal disease. “It used to be relatively easy to treat. Now, there are more drug-resistant strains to treat,” he says.

Researchers also are developing nontraditional vaccines. Pfizer, partnering with vaccine specialist Valneva (VALN), and Moderna are testing Lyme disease vaccines. Sanofi is developing one that combats the bacteria that causes acne skin disruptions.

The Food and Drug Administration recently gave fast-track status to a vaccine to treat the effects of Alzheimer’s disease. Instead of fending off a pathogen, vaccines could be used to make the body more tolerant of allergens like peanuts, scientists say. Meanwhile, a heart-disease vaccine would cause the body to produce less cholesterol. All of these vaccines are being researched.

And earlier this year, the government announced a $5 billion effort, dubbed Project NextGen, to develop new and better Covid vaccines. Among other things, the project will attempt to develop nasal vaccines that could better protect against infection and is targeting vaccines that could work on a variety of coronavirus diseases.

The biggest challenge facing vaccines is no longer the science but the growing number of Americans that refuse to take them.

Vaccine hesitancy has been a growing issue for years. It exploded during the pandemic, when thousands of Americans quit jobs rather than receive a Covid vaccination. While 92% of American adults have received at least one Covid vaccination shot , according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only about 21% got the booster shot being given earlier this year, and roughly 14% have received the current booster.

“You have the meteoric rise of science for developing and producing vaccines at the same time you have increasing skepticism and rejection of vaccines,” says Dr. Gregory Poland, who heads a vaccine team at the Mayo Clinic.

It hasn’t helped that Covid vaccines had some well-publicized side effects.

Janssen Covid vaccine was pulled from the market after some people developed blood clots, including a few who died. The CDC found higher-than-expected rates of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a serious nerve disease, in people who received the J&J vaccine. Meanwhile, a small number of people—mainly young men—who received the mRNA vaccines developed heart inflammation. The CDC said these effects were rare, and that hundreds of millions of people in the U.S. have safely received Covid vaccinations.

Vaccines are also a victim of their own success. Immunization currently prevents 3.5 million to five million deaths every year from diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, influenza, and measles, according to the World Health Organization. Because they have been successful in eliminating many of the most dangerous diseases, “we are not alert to the threats that microbes pose to us,” says the Mayo Clinic’s Poland.

Pharmaceutical companies are trying to make their vaccines more palatable to the American public. A lot of people dread needles, so drug companies are developing more vaccines that can be taken through a skin patch or a nasal spray.

If rising numbers of Americans refuse to take vaccines, it could ultimately crimp vaccine development, says Poland. “If they won’t take them in our society where our vaccines are produced by for-profit manufacturers,” he says, “manufacturers aren’t going to invest the roughly $1 billion it takes to go from a concept to a marketable vaccine.”

GSK’s Dormitzer agrees that vaccine hesitancy is a growing problem but says the current number of people who don’t take vaccines isn’t “enough to discourage drug companies from coming out with new vaccines.”

He notes that despite pushback against Covid vaccines, the majority of Americans were vaccinated at least once.

Growing vaccine hesitancy doesn’t seem to be impeding vaccine development, which is being juiced by new technology. The drug companies increasingly are using mRNA technology, tiny chunks of genetic material that tell the body’s cells to crank out specific proteins, such as the spike in the Covid virus, that produce an immunological response. “We can do very complex proteins because the mRNA is just a piece of software to code,” explains Moderna CEO Bancel.

And mRNA is by no means the only vaccine technology.

Take, for example, pneumococcal vaccines. Instead of proteins, pneumonia bacteria is surrounded by a layer of sugar. Earlier pneumococcal vaccines developed in the 1970s and 1980s weren’t very effective or long-lasting because they couldn’t target the proteins beneath that sugar layer, says Talaat, the Johns Hopkins vaccine expert.

Starting around 2000, drugmakers developed conjugated vaccines that combined pneumonia sugars with a piece of deactivated diphtheria protein that produces a strong immunological response. The resulting pneumonia vaccines were more powerful and long-lasting.

Invasive pneumococcal disease in children has dropped by nearly 80% in the U.S. since the introduction of those vaccines, according to the PhRMA report.

Researchers are using other techniques to make vaccines more potent. GSK’s adult RSV and shingles vaccines, for example, include adjuvants—compounds that produce a stronger immunological responses.

In general, vaccines work best against maladies that are naturally targeted by the immune system, such as infectious diseases and, more recently, cancers. But they could prove helpful in battling certain neurological diseases as well.

That may be the case with multiple sclerosis. Recent research has found that young people who are infected with the Epstein-Barr virus have much higher rates of multiple sclerosis—a serious neurological condition—when they get older.

Shingles, meanwhile, come from a latent form of the chickenpox virus. Because children are now being vaccinated against chickenpox, doctors are hoping that many fewer older adults will develop shingles.

Some targets prove elusive. Scientists have been unable to develop an effective vaccine against HIV. One problem is that the disease has the ability to hide deep within the lymph system, making it hard for the body’s T cells to attack.

Another problem is the virus itself, which keeps evolving in each infected individual. “HIV is a very diverse virus. It makes 10 billion copies of itself every day,” says Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu, a vaccine and HIV expert at Yale Medical School. “It makes it very challenging for the body’s immune system to neutralize the virus within a single person.”

Nonetheless, Ogbuagu is optimistic that an HIV vaccine will be developed. Instead of targeting one part of the virus, a HIV vaccine might have to target multiple parts to be effective as the virus evolves, he says.

Source: Barron’s