Crises of infectious diseases are becoming more common. The world should be better prepared.

Crises of infectious diseases are becoming more common. The world should be better prepared.

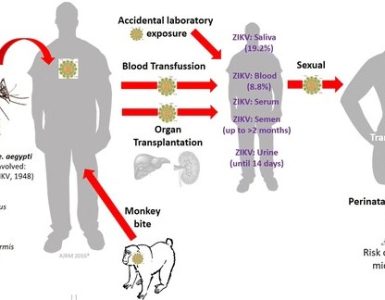

One of the sobering lessons of the Ebola crisis was how ill-prepared the world was for such a deadly disease. It is terrifying to reflect on how the virus’s advance was halted in the teeming city of Lagos thanks only to the heroism of a single doctor and because the place just happened to have the expertise needed to trace all of the first victim’s contacts. Today the world is facing a worrying outbreak of Zika virus, adding to a growing list of diseases that includes SARS, MERS and bird flu.

This is the new normal. New infectious diseases are becoming more common. With more people on the planet, more roads and flights connecting everyone, and greater contact between humans and animals, this is only to be expected. Over half of the 1,400 known human pathogens have their origins in animals such as pigs, bats, chickens and other birds.

Pandemics and pandemonium

When a new outbreak occurs, fear spreads even more rapidly than the virus. Politicians respond, rationally or not, with travel bans, quarantines or trade blocks. Airlines ground flights. Travellers cancel trips. Ebola has infected almost 30,000 people, killed more than 11,000 and cost more than $2 billion in lost output in the three hardest-hit countries. SARS infected 8,000 and killed 800; because it hit richer places, it cost more than $40 billion. Predicting these losses is hard, but a recent report on global health risks puts the expected economic losses from potential pandemics at around $60 billion a year.

As the threat grows, so does the case for beefing up defences against disease. America’s National Academy of Medicine suggests that just $4.5 billion a year (equivalent to about 3% of what rich countries spend on development aid) devoted to preparing for pandemics would make the world a lot safer. The money would strengthen public-health systems, improve co-ordination in an emergency and fund neglected areas of R&D.

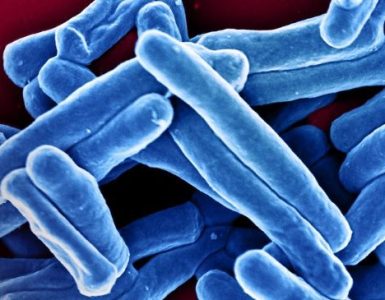

Many of the investments to prepare for pandemics would bring broader benefits, too. Stronger public-health systems would help fight such diseases as tuberculosis, which reduces global GDP by $12 billion a year, and malaria, which takes an even bigger toll. But the priority should be to advance vaccines for diseases that are rare today, but which scientists know could easily become pandemics in the future: Lassa fever, say, Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever or Marburg.

Better sharing of data would help (see article). More important is funding and a review of who has liability if firms rush vaccines or drugs to market. The initial development and early-stage testing of vaccines for the most likely future pandemics would cost roughly $150m each. Drug firms have little incentive to invest in a vaccine that may never be used. For these firms even later-stage testing when a pandemic breaks out is tricky. The drug industry spent $1 billion on Ebola and took on liability risk, yet never made a profit. The same companies may not be so willing next time. To encourage drug firms to play their full part during an emergency, governments need to set out how they will share the burden.

Since the financial crisis, banks have been required to hold more capital in order to lower the risk of economic contagion. The world spends about $2 trillion annually on defence. Investing in health security is a similar form of insurance, but one with better returns.

Source: The Economist