Damage to our climate, shifting patterns of animal and human interaction, urbanization, the creep of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and increased international trade and travel are all creating more opportunities for new and dangerous epidemic and pandemic risks to emerge.

To stand a chance of rapidly predicting, detecting and preventing the diseases of tomorrow from potentially escalating, we need a global step change in surveillance.

Building infectious disease surveillance systems

We are by no means starting from scratch. COVID-19 has shone a light on how valuable high-quality, near real-time data is to all elements of an effective response for clinicians, researchers, policymakers and the public alike. Though it has exposed fundamental weaknesses in all parts of the world, it has also shown us clearly the systems that do work well.

The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System already manages the surveillance of new strains of influenza. The Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System similarly collects national data on AMR for selected priority pathogens.

Most recently, it was the well-established disease testing and surveillance networks in South Africa that alerted the world to the dangers of the Omicron variant.

With unprecedented speed, this data could then be investigated using classic approaches and genomic sequencing, which help to measure and map how infections emerge and evolve. This equipped public health teams to respond and allowed diagnostic, treatment and vaccine developers to assess the impact of Omicron on our existing tools.

South Africa’s impressive surveillance capabilities reflect a long-term investment in people and facilities that started well before the pandemic.

This has seen genomic sequencing technology and fundamental surveillance capabilities embedded within communities to provide continuous utility and value. The speed at which these systems could pivot to COVID-19 demonstrates the payoff of sustained investment in public health for endemic health issues.

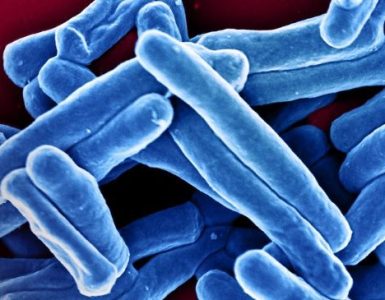

Elsewhere in the world, the ability to survey infectious disease diverges. Even existing issues that are well understood – such as pneumonia, diarrhoeal illness, tuberculosis, HIV, malaria and drug resistance are currently monitored poorly.

This matters. We need to be able to spot the epidemic and pandemic threats of tomorrow to prevent their escalation.

Significant investments started to close this gap. Across Latin America and the Caribbean, The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has built a regional surveillance network. Initially establishing reference laboratories to increase global COVID-19 data, the focus has now moved wider to building in-country disease sequencing capacity.

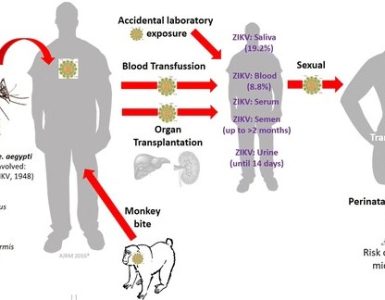

For example, the Dominican Republic now has the research capability to monitor annual outbreaks of arboviruses like chikungunya, zika and dengue. This information is critical to managing the burden of these diseases in-country and monitoring whether they may spread to other countries.

The technology, platforms and materials needed to keep infectious disease in check equally require dedicated public health professionals, clinicians, researchers and a sustained commitment to training and career development.

During this pandemic, COG-Train has provided open-access learning courses in COVID-19 genomics, partnering internationally to facilitate knowledge sharing in a rapidly changing environment. In Kenya, researchers have collaborated with Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia and the Seychelles, alongside The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, by providing technical support and training during challenging lockdowns.

Disseminating this knowledge and these skills and integrating these locally rooted teams within national and international frameworks is critical to addressing global inequities in surveillance. Silos will only slow down the response to infectious disease, where timing is everything.

This means joining up local, country-level surveillance with collaborative public health organizations, and sharing data and insights with global platforms like the new WHO Surveillance Hub in Berlin and GISAID to ensure rapid, open and trusted access to reliable information.

To do this, governments, industry and philanthropy will need to sustain momentum and continue to work together. Previous outbreaks have demonstrated partnership results in rapid, breath-taking scientific advances for the good of the entire global community. Why stop now?

Take CEPI. Founded five years ago after the West Africa ebola outbreak and launched at the World Economic Forum in 2017 to fill the gap in the development of vaccines for emerging infectious diseases, the organization built the world’s largest and most diverse portfolios of COVID-19 vaccines.

Imagine if we prioritized surveillance in the same way and made it part of the day-to-day work of public health.

Investment is key to prevent future pandemics

Last year’s G7 Summit attracted support for the ambitious proposal of a new Global Pandemic Radar. Almost a year on, now is the time to turn these warm words into concrete financial commitments and a fresh resolve to make it happen. Giving in to fatigue will only repeat the panic and neglect cycle of the last 20 years.

The value of these investments will be contingent on political leaders pledging to follow the insights they generate. As the last two years have shown, acting early and decisively in the face of any new or emerging disease saves lives, protects our healthcare systems, and avoids preventable damage to economies and livelihoods.

Surveillance has more than proved its worth, but only if you follow it. With the possibility of a new epidemic or pandemic just around the corner, we cannot leave this to chance.

Source: World Economic Forum 2022