From COVID to Lyme disease to various fungal afflictions, climate change has already worsened over 200 infectious diseases.

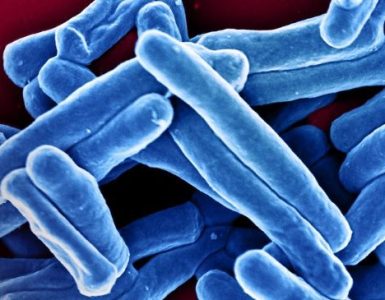

Heat waves, floods, droughts, and rising temperatures fueled by climate change have made the world more vulnerable to disease outbreaks and the spread of a wide variety of pathogens — from bacteria and viruses to fungi and protozoa.

Climate change has already increased the risk of nearly 60% of all known infectious diseases, including tick- and mosquito-borne diseases — like Lyme disease and dengue — and various food- and waterborne infections, according to an analysis published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The risks will grow as summers get longer and warmer, winters get shorter and milder, and weather events worldwide get more extreme and unpredictable. Growing risks from infectious diseases that thrive in these environments will come not only from known pathogens, experts say; new infectious diseases are also more likely to emerge.

“Outbreaks of emerging and reemerging infectious disease threats are only accelerating,” says Syra Madad, an infectious disease epidemiologist and senior director of the system-wide special pathogens program at New York City Health + Hospitals.

Years of a global assault from COVID combined with increasingly severe climate disruptions have given people worldwide a preview of what a future of unabated climate change may bring.

To promote better health, individuals and society will need to juggle immediate vigilance with long-term steps like sharply cutting heat-trapping carbon pollution and environmental degradation while putting more resources into educating the public about the risks of their local pathogens and the benefits of better nutrition, hygiene, and staying up to date with vaccines.

Climate fever

Climate change is creating increased exposure pathways by bringing humans and pathogens closer together while also selecting for pathogens that evolve to survive in higher temperatures.

Some infections spread through vector-borne transmission, meaning through the bites of mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, and other organisms. Warmer temperatures across greater geographical areas, shorter winters, and earlier springs encourage people to spend time outdoors and also allow these vectors to claim a foothold in more territory. This puts more people at risk of exposure to illnesses like Lyme disease, West Nile virus disease, and ehrlichiosis. The number of U.S. illnesses reported from flea, mosquito, and tick bites doubled between 2004 and 2018, according to the CDC.

Higher temperatures and an increase in recreational activities around water also bring more people closer to the source of waterborne infections that can cause illnesses like diarrhea, intestinal infections, and in rare and more severe cases infections like primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, caused by an amoeba that can find a home in warm fresh water like lakes and rivers.

Increased temperatures also increase the risk that infectious diseases will evolve to tolerate and thrive in warmer environments. This makes it harder for humans to fight infections with one of the best defense mechanisms against invading infections: mounting a fever. Pathogens that evolve a better ability to overcome this defense will be ever more dangerous.

Along with risks for the spread and increased virulence — or strength — of known infectious diseases, we are living in an era with higher risks for exposure to completely novel infections.

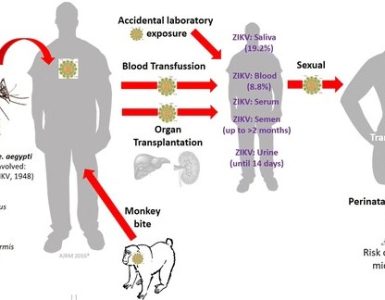

“Our ecological footprint is expanding, and spillover events are increasing,” Madad says. Spillover events are those in which a pathogen jumps from an original host to a new species, as happened with MERS, or Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome, from a virus first reported in humans in 2012. A spillover event is also a likely explanation for the origin of the virus that causes COVID-19, which closely resembles viruses that circulate in bats.

The dangers of an infectious disease to a host depend on many factors, but the first is the pathogen’s ability to actually infect a host cell. As humans encroach more and more on the natural habitats of wildlife, new pathogens gain opportunities to develop the right mutations to jump from an animal host to infect a human host. With additional opportunities, other mutations may arise that eventually allow for human-to-human transfer of a completely new pathogen. The combination of climate change forcing wildlife out of their habitats and the expanding footprint of humans into the habitats of wildlife will only increase the risks for novel infections in spillover events.

Increasing human vulnerability

Human vulnerabilities also affect the ability of a pathogen to cause disease. In general, infection with a completely novel pathogen, meaning no previous exposure, means that a person has no immune protection from previous infection (though there are some exceptions, as exposure to a similar family of viruses may confer some cross-immunity).

Other factors also play a role in underlying susceptibility. For example, preexisting chronic disease or frailty because of extremes of age can also greatly alter the severity of a given infectious disease. Climate change can exacerbate these problems, too: Extreme weather events can lead to displacement, droughts can lead to food insecurity, and wildfires may worsen air quality. All these factors can make people more vulnerable to more severe infections. And as with COVID and other global problems, climate change impacts often hit hardest at the people who are already marginalized or most vulnerable.

James Ford, a climate change adaptation researcher and professor at the Priestley International Centre for Climate at the University of Leeds, studied how the combined vulnerabilities to climate change and COVID-19 play out among Indigenous people in 12 nations, including those from the Arctic, Peru, India, and parts of Africa.

Ford said his research suggests that previous climate disasters had consequences for COVID management, because of the destruction of health posts and other critical infrastructure needed to serve local communities.

Climate events can also threaten a community’s ability to respond to infectious disease threats with routine public health safeguards. For example, extreme weather events can crowd people into unsafe shelter areas where it is impossible to maintain social distance. Also, heat waves may make it less desirable to spend time outdoors or wear masks indoors to stay safe from airborne infectious diseases.

What can people do?

The world’s experience in responding to COVID and climate disasters provides a guide for strategies that can protect health.

Countermeasures that decrease exposure to escalating climate and infectious disease threats in both the short and long term are critical. That includes reducing carbon pollution, minimizing environmental degradation and land use changes, and encouraging public education about the local risks of various pathogens. Individuals and communities can also take actions such as staying up to date with vaccines, optimizing health with high-quality nutrition, and ensuring access to health services in the event that infectious disease does take root in a community.

“Even with the most marginalized communities this can be a story of resilience as well as vulnerability,” Ford says.

Source: Yale Climate Connections