The first human test of an experimental vaccine against a deadly strain of avian flu, using novel technology that could produce millions of doses very quickly, produced protective antibodies in the vast majority of those who received it, scientists said on Wednesday.

The first human test of an experimental vaccine against a deadly strain of avian flu, using novel technology that could produce millions of doses very quickly, produced protective antibodies in the vast majority of those who received it, scientists said on Wednesday.

The encouraging results in the early stage trial from Novavax, a biopharmaceutical company based in Rockville, Maryland, were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“These are very preliminary results, but it appears for the first time that we may have a vaccine that would work against an outbreak” of avian flu, said Robin Robinson, director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, the federal agency in charge of developing countermeasures against public health emergencies.

Because other candidate vaccines against avian flu have failed, “this is a very important milestone,” he said. “We have a promising vaccine where before we had none.”

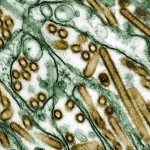

The H7N9 strain of avian flu emerged in China last winter, causing 45 deaths in 137 confirmed cases this year through late October, according to the World Health Organization. Cases and deaths, often from severe pneumonia, both peaked last March and April.

But public health experts fear the virus could come storming back this flu season. After no reported cases of H7N9 in China in August or September, there have been four since early October.

A mortality rate of one-third suggests the virus is highly lethal.

The WHO says there is currently “no indication” the virus can be transmitted from person to person, and so cannot become a pandemic. But flu strains are notorious for undergoing genetic changes, including those that make them transmissible between people.

In the clinical trial, conducted in Australia, 284 adult volunteers received two doses of either a dummy injection (placebo) or one of six formulations of the experimental vaccine – a high or low dose with or without an adjuvant, a chemical compound that turbocharges the immune system. The heart of the vaccine is two proteins, dubbed H7 and N9, that stick out from the virus and give it its name.

Apart from some redness and soreness around the injection site in some volunteers, mostly among those receiving the vaccine containing adjuvant, the vaccine had no ill effects, Novavax reported.

It produced meaningful levels of antibodies, molecules of the immune system that attack invaders. The vaccine triggered production of antibodies against the “H” protein in 81 percent of the volunteers who received the vaccine with the high level of adjuvant, and antibodies against the “N” in more than 90 percent.

The study did not expose volunteers to virus, which is considered unethical, to see if the antibody levels warded off infection. “But these antibody levels are very likely to be protective,” said Dr Louis Fries, Novavax’s vice president for clinical and medical affairs, who led the study.

FAST MANUFACTURING

Just as important as the vaccine’s apparent efficacy is how quickly it can be produced, thanks to eliminating the need to use chicken eggs as most vaccine production does. Fast manufacturing is important because a pandemic flu strain can emerge with little warning. An initial outbreak of a new flu strain is often followed by a more severe and widespread outbreak the following flu season.

That happened with the H1N1 swine flu in early 2009. Vaccine makers could not produce vaccine before H1N1’s “second wave” that autumn, and the virus eventually infected an estimated 61 million people in the United States and caused some 12,000 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But after scientists determined the genetic sequence of H7N9 last March, and deposited it in a public database, it took Novavax only a month to produce an experimental vaccine ready to test in animals. The human volunteers received their first doses in early July.

“Our technology let us produce vaccine in just a month and start testing it in four,” said Fries.

That was possible because Novavax does not go through the time-consuming process of using chicken eggs to manufacture vaccine. Instead, it takes the virus’ genetic sequence and produces what it calls a “virus-like particle vaccine.”

Virus-like particles, or VLPs, contain three proteins that trigger the production of antibodies and other immune responses to thwart the virus. The H and N proteins generate antibodies that keep the virus from replicating and infecting cells, while a third protein stimulates killer T cells to slay any cells already infected.

“We think this is two shots on goal on terms of protection” against H7N9 protection, said Fries.

Using Novavax’s technique, said BARDA’s Robinson, computer models suggest manufacturers could produce the first doses of H7N9 vaccine within 12 weeks of the emergence of a pandemic, 50 million doses within four months, and hundreds of millions of doses within six months.

The trial used two doses, given 21 days apart. Since H7N9 is a new flu strain, it is probable that no one in the general population carries antibodies to it, said Fries, making two doses necessary.

Novavax has a three-year, $97 million contract with BARDA to develop recombinant influenza vaccines and manufacturing capabilities sufficient to produce enough vaccine for a pandemic. It is planning a second trial of the VLP vaccine in early 2014 to nail down the minimum effective dose, said Fries.

Five other candidate H7N9 vaccines are being developed, said Robinson, with results expected in four to six months. “If this one works, the others are likely to as well” because they are based on similar technology. If so, public health authorities around the world would then likely have multiple vaccines to choose from should an avian flu pandemic emerge.

Source: Reuters