A new flu, H7N9, has killed 36 people since it was first found in China two months ago. A new virus from the SARS family has killed 22 people since it was found on the Arabian Peninsula last summer.

A new flu, H7N9, has killed 36 people since it was first found in China two months ago. A new virus from the SARS family has killed 22 people since it was found on the Arabian Peninsula last summer.

In past years, this might have been occasion for panic. Yet chicken and pork sales have not plummeted, as they did during earlier flus. Is this relatively calm response in order? Or does the simultaneous emergence of two new diseases suggest something more dire? Actually, experts say, the answer to both questions may well be yes.

“Compared to H5N1 and SARS, we’re getting on top of these diseases much, much faster,” said Dr William B Karesh, a wildlife veterinarian and chief of health policy for the EcoHealth Alliance, which tracks animal-human outbreaks. But he added that “people have become desensitised over time—it’s ‘Oh, OK, another one’.”

And, scientists say, the world cannot afford to relax. For, new diseases are emerging faster than ever.

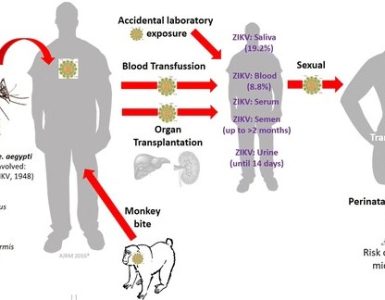

Peter Daszak, a parasitologist and president of the EcoHealth Alliance, has even put a number on it: 5.3 new ones each year, based on a study using data from 1940 to 2004. He and his co-authors blamed population growth, deforestation, antibiotic overuse, factory farming, live animal markets, bush meat hunting, jet travel and other factors.

Some aspects of the new viruses are scary. The Arabian coronavirus—now officially named MERS, for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome—has killed about half of those it infects, while SARS killed less than a quarter; in the lab, it replicates faster than SARS, penetrates lung cells more readily and inhibits the formation of proteins that warn the body that it is under attack. The H7N9 flu has been fatal in a quarter of known cases and already has one dangerous mutation that helps it replicate at human body temperatures. Still, better surveillance means that such threats are being caught sooner.

The world’s ability to detect new diseases has sped up for reasons both technical and political. First, rapid gene sequencing is now done in many laboratories. Second, accurate symptom descriptions are instantly available. Web-based news services like ProMED, with scientist-members all over the world, issue several daily reports of outbreaks of everything from banana wilt to sheep bluetongue to human Ebola. Scientists learned, for example, that a 2008 convention of Roman Catholic youth in Sydney, Australia, drew in influenza strains that then seeded new outbreaks all over the Northern Hemisphere.

Third, and very important, countries that used to hide their outbreaks now admit them. Covering up an outbreak is now a violation of World Health Organisation regulations adopted in the wake of SARS. The rules require members to disclose any public health event that could spread beyond their borders.

Both H7N9 and MERS fit that description. Neither is easily transmissible, though both have undoubtedly infected family members, nurses or hospital roommates after long exposure.

More worrisome is that no one knows how these viruses first infect victims. The origins of MERS are even more baffling. Scientists assume it is from bats, because it is genetically closer to coronaviruses found in them than to SARS or to the four known human coronaviruses, which cause common colds. But while bats in Mexico, Europe and Africa have similar viruses, none has yet been found in Arabian animals.

Right now, doctors are relying on isolating patients and antiviral treatment with oseltamivir and zanamivir for H7N9, and ribavirin and interferon for MERS.

If either virus goes epidemic, the next step would be vaccine. The US Centers for Disease Control and Protection began making one against H7N9 in early April. The first of several candidates may be ready for manufacturers by the end of May, a spokeswoman said.

Source: The Indian Express