Science shows that even the most serious side effects for any vaccine, including COVID-19, occur within just a few weeks.

Science shows that even the most serious side effects for any vaccine, including COVID-19, occur within just a few weeks.

Seven months after the U.S. began administering COVID-19 vaccines, the latest figures from the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation’s ongoing tracking poll show that 10 percent of adults are still nervous about the vaccine and want to “wait and see” how others fare before rolling up their sleeves. Young adults ages 18 to 29 and Black and Hispanic people are some of the most likely to voice this sentiment.

The main two reasons cited for this hesitancy are that the vaccines are “too new” and that they may trigger unexpected or life-threatening side effects, perhaps even months or years later. It’s true that reports of new side effects can sometimes take months to emerge as a vaccine goes from populations of thousands in clinical trials to millions in the real world, encountering natural variations in human responses along the way. But more than a hundred million Americans have already passed that point in their vaccinations and the first participants in the clinical trials are now beyond a year.

So far, incidents of severe side effects for the coronavirus vaccines such as Guillain-Barré Syndrome and heart inflammation are very rare, and they were discovered quickly because they were on official lists of potential problems to watch for. What’s more, all these and other side effects appear soon after someone has taken the vaccine, suggesting that people don’t need to worry about delayed long-term reactions.

This picture fits with the modern history of vaccinations, which shows that most new immunizations have been incredibly safe, and even the most severe effects have reared their ugly heads right away.

“Side-effects nearly always occur within a couple of weeks of a person being vaccinated,” says John Grabenstein, director of scientific communication for the Immunization Action Coalition. He adds that the longest time before a side effect appeared for any type of shot has been six weeks.

“The concerns that something will spring up later with the COVID-19 vaccines are not impossible, but based on what we know, they aren’t likely,” adds Miles Braun, adjunct professor of medicine at the Georgetown University School of Medicine and the former director of the division of epidemiology at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

A key reason for this limited window of side effects is the short time all vaccines stay in the body, says Onyema Ogbuagu, an infectious diseases specialist at Yale Medicine and a principal investigator of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine trial. Unlike medicines that people take every day or week, vaccines are generally administered once or a handful of times over a lifetime. The mRNA molecules used in the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are especially fragile, he notes, so “they are out of your body in a day or so.”

The vaccines subsequently get to work stimulating the immune system so it can memorize the virus’s blueprint and mount a quick response if it encounters the real thing later. “This process is completed within about six weeks,” says Inci Yildirim, a vaccinologist and pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Yale Medicine. That’s why serious adverse effects that might be triggered by the process emerge within this time frame, after which everything is put on a shelf in the body’s library of known pathogens, Yildirim says.

Historically, vaccine side-effects appear right away

A stroll through vaccine history confirms that even the most damaging side effects have indeed taken place within a six-week window.

After the initial Salk polio vaccine was introduced in 1955, it became clear that some of the first batches inadvertently contained live polio viruses and not the weakened form intended to be in the shot. Within weeks, this mistake resulted in some polio infections and, in a few cases, eventual death. The “Cutter incident,” named after the manufacturing labs with the biggest mishaps, prompted more stringent government regulations. Today, polio vaccines are monitored to make sure the virus is completely inactivated in shots given to children.

In 1976, rare cases of the nerve disorder Guillain- Barré Syndrome emerged some two to three weeks after people began receiving an egg-based inactivated flu vaccine against a dangerous strain of H1N1 swine flu. Scientists eventually determined the effect occurred in one to two people per million shots. Guillain- Barré is a treatable disease, but with flu season winding down that year, the vaccination effort was soon abandoned.

This same condition was recently tied to the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine, with a hundred preliminary reports after approximately 12.5 million doses were administered, according to the FDA. In these cases, the syndrome emerged some two weeks after vaccination, primarily in men over 50.

In 2008, seven to 10 days after receiving a shot combining the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR) with one for chicken pox (varicella), some babies developed febrile seizures. These seizure cases occurred in one child per 2,300 vaccine doses, which is why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices currently recommends most children get the two shots separately.

Within weeks of receiving the yellow fever vaccine, a very small number of people develop inflammation of the brain (encephalitis), swelling of the spinal cord covering (meningitis), Guillain-Barré Syndrome, or a multiple-organ system dysfunction called viscerotropic disease. Travelers to places where this fatal disease is endemic are still urged to get the vaccine, although the CDC recommends people over 60 weigh the risks and benefits with their healthcare provider.

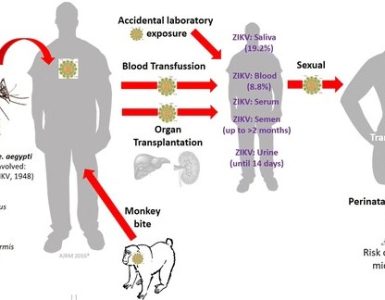

The rare exception to adverse events occurring within the six-week timetable is the dengue fever vaccine, Dengavaxia, which the Philippine government approved for use in their children in 2016. When people are infected with the dengue virus, their first bout of this disease is fairly mild. But when they get infected a second time, with a different strain, the reaction can be much more severe and, in some cases, fatal.

As some experts predicted, the vaccine—made from inactivated viruses—acted like a first infection, meaning many kids subsequently bitten by a dengue virus-carrying mosquito fared worse than if they hadn’t been inoculated. In 2019, the FDA approved the vaccine, but only for children in dengue-infested U.S. territories who had a laboratory-confirmed prior case of the disease.

So, no vaccine has caused chronic conditions to emerge years or decades later, says Robert Jacobson, medical director of the population health science program at the Mayo Clinic. “Study after study have looked for this with all sorts of vaccines, and have not found it to be the case,” he says.

For example, a 2016 meta-analysis examined 23 studies for evidence that common childhood vaccines like MMR or haemophilus influenza B might somehow cause childhood diabetes; it found no connection. To test the concern that vaccinations might bring on autoimmune conditions such as multiple sclerosis in adults, a 2017 review evaluated nine common vaccines, including tetanus, human papillomavirus, and seasonal flu. It found that cases of MS did not rise as a result of widespread vaccine use.

Monitoring for COVID-19 is even more extensive

With COVID-19, regulators have added several extra pairs of eyes to watch for adverse events and report them as quickly as possible.

“For all vaccines there is a phase four,” Yildirim says, that involves extensive monitoring after a vaccine completes its phase-three clinical trial and is granted FDA approval. This monitoring primarily happens via the Vaccine Adverse Reporting System (VAERS), where any individual or physician can fill out a form flagging potential side effects. Scientists then evaluate whether any reported effects occur beyond what is generally expected in the population.

Massive computer power is put to use for the second leg of the stool, the Vaccine Safety Datalink. This program is a collaboration between the CDC and nine large healthcare providers, the majority of which are part of the Kaiser Permanente system. One aspect of this program is a rapid cycle analysis, which tracks the records of millions of participants’ patients immediately after a new vaccine is administered.

“This analysis is done weekly. If there are signals [of an adverse event] we see it quickly,” says Nicola Klein, director of Kaiser Permanente’s vaccine study center in Oakland, California, who is leading the analysis for COVID-19. The Datalink program flagged the febrile seizures with the MMRV vaccine, information that was brought to the public within months, Klein says.

New for COVID-19, the CDC developed the V-safe app; once downloaded, vaccine recipients are asked by text messages and web surveys about any adverse events. Other programs involve long-term care facilities and large insurers tasked with flagging issues emerging in their patient populations.

“The breadth of vaccine safety surveillance systems means the limitations of one approach are offset by the strengths of others, making the combination quite robust,” says Grabenstein, of the Immunization Action Coalition.

What side effects have been flagged for COVID-19 shots?

Experts begin this robust monitoring process with a ready list of potential side effects. “These conditions are selected based on what was seen in clinical trials (even if they weren’t statistically significant there), those caused by the disease itself, and what has appeared in prior vaccines,” says Frank DeStefano, director of the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office.

For the COVID-19 vaccines, these “events of special interest,” which number nearly two dozen, include arthritis, narcolepsy, encephalitis, and stroke.

Also on this list: the blood clotting condition thrombosis. Klein says this was added after the issue emerged with the AstraZeneca vaccine in Europe, since the Johnson & Johnson shot authorized in the U.S. employs a similar adenovirus vector technology. Soon after, regulators saw the effect in a minute number of young women who got the Johnson & Johnson shot, with clots appearing by the second week after their vaccinations.

Guillain-Barré was always on the watch list, since it previously appeared with other vaccines. Similarly, the heart inflammations myocarditis and pericarditis, which have occurred several days after vaccination in a tiny fraction of young men getting the mRNA vaccines, was already on the list.

Of course, experts say they also watch for the unexpected. Grabenstein recalls the time in 2004 when he led a smallpox vaccination effort for the U.S. Army. Several servicemembers quickly developed myocarditis, even though this condition had not appeared during the smallpox inoculation efforts in the 1940s and ‘50s. “The best explanation is that earlier vaccines were given to infants, while we were inoculating 20-year-olds,” he says.

With so many coronavirus vaccines administered in so short a time, it has actually been easier to spot incredibly rare adverse events, Yildirim says. The Johnson & Johnson events were flagged within months of the vaccine’s authorization—which shows that the system is working. “We don’t like to hear about side effects, but the fact that we hear about them is a good sign because this means they are being identified,” she says.

And DeStefano feels confident that severe adverse events shouldn’t start appearing for the vaccines authorized late last year. “We have systems looking for delayed effects,” he says. “But our experience from other vaccines shows that late-arriving effects from the COVID-19 vaccines are unlikely.”

Source: National Geographic