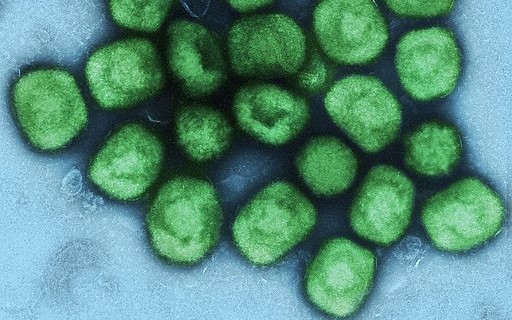

Favored shot is a seemingly safer smallpox vaccine, but efficacy remains unclear

In 1959, German microbiologist Anton Mayr took a strain of vaccinia, a poxvirus used to inoculate against smallpox, and started to grow it in cells taken from chicken embryos. After several years of transferring the strain to fresh cells every few days, the virus had changed so much it could no longer reproduce in most cells from mammals. But it could still produce an immune response that protected against smallpox.

Mayr had set out to study how poxviruses evolve, but by accident he had produced a potentially safer smallpox vaccine. Dubbed Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA) because the original viral strain came from that Turkish city, the vaccine had a short career. “With smallpox eradicated in 1980, it disappeared into the freezer,” says Gerd Sutter, a virologist at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, who has studied Mayr’s vaccinia strain for decades.

Now, this virus, further weakened and brought to the market by the Danish pharma company Bavarian Nordic, may become key to arresting the largest outbreak of monkeypox ever seen outside Africa, which has already sickened more than 1000 people. It is the only vaccine licensed anywhere for use against monkeypox, although other, riskier smallpox vaccines also appear to offer some protection.

The United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and several other countries have already started to “ring” vaccinate, offering it to contacts of identified monkeypox cases, including health care workers and sexual partners.

“MVA will be very important in this outbreak because it is a nonreplicating vaccine, which means it doesn’t have the same side effect profile as some of the other live [virus] vaccines” being considered, says Rosamund Lewis, technical lead on monkeypox at the World Health Organization (WHO).

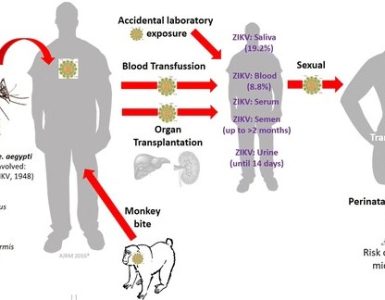

But what role the vaccine will ultimately play depends on a host of factors: whether those most at risk from infection can be identified and vaccinated, whether the vaccine is as effective as hoped, and whether enough is available to stop the burgeoning outbreak. WHO has so far only backed ring vaccination—MVA is ideally given within 4 days of an exposure but recommended for up to 14 days—but some scientists say it’s too difficult to reach the specific contacts people had. They advocate broader vaccination campaigns in the population most affected so far: men who have sex with men (MSM).

Hundreds of millions of doses of smallpox vaccine are stored around the world, insurance against a possible release of the dreaded virus by terrorists or in war, and they are known to offer some protection against monkeypox. A study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in the 1980s found that household contacts of people sick with monkeypox were seven times less likely to contract the disease if they had been vaccinated against smallpox. Yet the vast majority of existing smallpox vaccines consist still replicating vaccinia. These can cause rare but life-threatening side effects such as encephalitis or progressive vaccinia, the spread of the vaccine virus to the whole body, to which immunocompromised people are vulnerable.

Although 66 people have already died of monkeypox this year in African countries, the recent cases in nonendemic countries have mostly been mild. And many contacts of those infected are living with HIV, which could make them more likely to suffer from vaccinia side effects. Given the risks and benefits, “using these vaccines is out of the question,” Sutter says.

Bavarian Nordic’s nonreplicating vaccine, marketed as Jynneos in the United States and as Imvanex in Europe, sidesteps some of the risk. So does a vaccinia-based vaccine named LC16m8, licensed for smallpox only in Japan, which also appears to cause fewer side effects. “I believe these are the ones that are going to be used [in the new outbreak] because they have a much-enhanced safety profile,” says Marion Gruber, who headed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine office until October 2021.

Canada and the United States have already licensed MVA for use against monkeypox and Bavarian Nordic is in talks with the European Medicines Agency (EMA). “I really hope that in a matter of 1 or 2 months from now, this can be approved” in Europe, says EMA’s Marco Cavaleri.

The United Kingdom has been using MVA “off-label” for a few years to vaccinate contacts of imported monkeypox cases. WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization is set to release guidance in the next days that will back MVA, but it will also recommend using earlier vaccines in certain scenarios. Still, Cavaleri says, “If [MVA] is available, clearly that will be the vaccine to start.”

Exactly how much is available remains murky. “Countries have been reluctant over the past couple of decades to share that information in detail with WHO, but WHO is now reaching out to all of them again,” Lewis says. The United States, which supported development of MVA, likely has the biggest supply. A federal spokesperson says the Strategic National Stockpile has 36,000 doses, that another 36,000 doses will be delivered “in the near future,” and that the company is storing bulk material for millions more U.S.-reserved doses. A Bavarian Nordic spokesperson says many other countries had ordered its MVA vaccine in the past weeks and the company was trying to send smaller batches to countries “so they can start to vaccinate sooner rather than later.”

How broadly to roll out MVA, or any vaccine, remains the key debate. Ring vaccination among MSM can be challenging given the stigma faced by that group in many cultures and the nature of the contacts. A paper published last week in Eurosurveillance noted that in the United Kingdom, many of those infected reported sexual contacts with people whose details they either did not know or did not want to share.

The Canadian province of Quebec has already extended vaccinations from direct contacts of monkeypox cases to any men who have had more than two male sexual partners in the past 14 days. Another way to tackle the problem, says Yale School of Public Health epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves, “would be to offer it to individuals who have attended social events in which close contact with someone infected was possible, but this would increase the numbers of those being recruited for vaccination even further.” Germany is also likely to offer the vaccine more broadly, though it will not quickly have enough vaccine available for all MSM, says Leif Erik Sander, an infectious disease expert at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin.

Even where contacts of infected cases were identified, uptake has been low. The same U.K. study reported that 169 out of 245 health care workers who had been offered MVA had taken it, but only 15 out of 107 contacts in other groups. “It’s very challenging to target high-risk groups while balancing stigma and encouraging uptake of the vaccines,” says Boghuma Titanji, a virologist at Emory University. The politicization of vaccines during COVID-19 has increased the barriers, she adds.

How well MVA really protects humans from monkeypox is uncertain. The license for MVA in Canada and the United States is based on animal studies, where it was shown to protect macaques and prairie dogs, plus data in humans showing a strong antibody response. A pair of DRC studies vaccinated 1600 health care workers with one of two MVA formulations and found no monkeypox cases in each 2-year study period.

But there were no control groups, and one vaccinated health care worker did get monkeypox half a year later. “The truth is, we don’t know the efficacy of any of these monkeypox vaccines,” says Ira Longini, a biostatistician at the University of Florida who is advising WHO.

That is why WHO has urged countries that deploy monkeypox vaccine to study how well it works and how best to use it. “If we want to contain these outbreaks and learn something about the efficacy of these vaccines, it’s going to have to be a concerted effort with protocols and organized properly,” Longini says. One question is whether a single dose of the vaccine, which is normally given as two doses 4 weeks apart, may suffice. That could encourage more uptake and stretch supplies.

The question of vaccine equity looms large, too. Titanji notes that the hopes for MVA are based partly on the DRC data. “It’s almost a moral obligation to make sure that, if these vaccines are being utilized elsewhere now, the people on whom the data was generated, who have been dealing with monkeypox for 50 years, should have access to it as well.”

Source: Science