Dr Malick Gibani explains how a human challenge study for non-typhoidal Salmonella can support vaccine development and protect vulnerable populations.

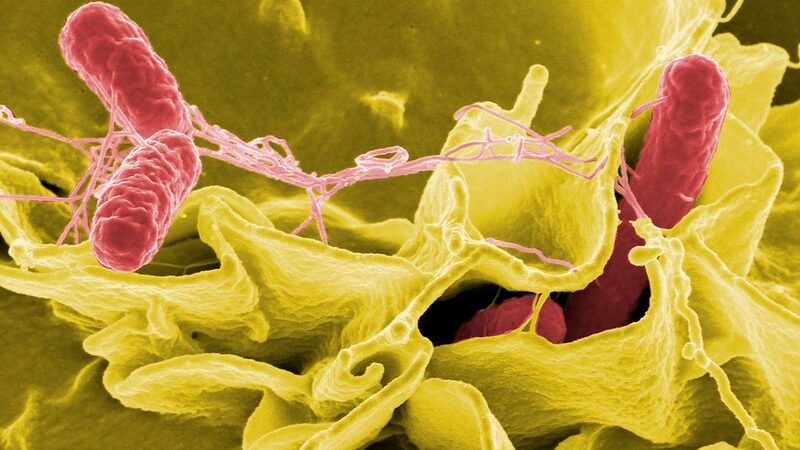

Salmonella infection (salmonellosis) is a common disease caused by most types of Salmonella, hardy bacteria that live in the intestines of humans and animals. The types of Salmonella which cause salmonellosis are sometimes referred to as ‘non-typhoidal’ to distinguish them from other strains which cause typhoid fever.

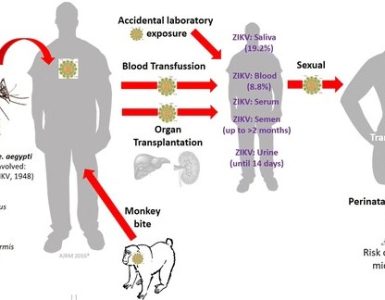

Salmonella infection is generally spread through the consumption of contaminated food, often from animal sources, such as eggs, meat and milk. Most people experience mild symptoms such as a fever, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and nausea, and recover over the course of a few days.

Global impact

However, Salmonella infection can sometimes be life-threatening. Certain strains of Salmonella bacteria found in sub-Saharan Africa are invasive, meaning that they can enter the bloodstream and spread through the body. This can result in serious complications, most commonly septicaemia, anaemia and kidney failure. Vulnerable populations in sub-Saharan Africa – such as malnourished children under the age of five and those with malaria or HIV infection – are particularly at risk of severe disease.

In 2017, there were an estimated 535,000 cases of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease globally and 77,500 deaths, the majority of which (approximately 66,500) occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that Salmonella is one of the four key global causes of diarrhoeal diseases, which collectively account for 550 million people falling ill each year, including 220 million children under the age of five.

Human challenge studies

Human challenge studies involve deliberately infecting healthy volunteers with a carefully considered dose of a pathogen, such as a virus or bacteria. This allows scientists a unique opportunity to observe and study how different diseases develop in humans. A recent example of this is the COVID-19 human challenge study led by Imperial, the findings of which were published in Nature Medicine earlier this year. Once an infection model has been established and shown to be safe, it can then also be used to test the efficacy of different vaccines.

Dr Malick Gibani is a Clinical Lecturer in the Department of Infectious Disease at Imperial College London and a Specialist Registrar in Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. He is currently working to establish a Wellcome-funded human challenge model for non-typhoidal Salmonella.

We spoke to Dr Gibani about why a human challenge study is needed to tackle the global impact of non-typhoidal Salmonella.

Q: Why do we need a human challenge study for non-typhoidal Salmonella?

Salmonella infection is a huge problem in terms of the global disease burden. It typically occurs when there is a breakdown in food hygiene standards. For most people, the infection leads to gastroenteritis, and they’ll feel better after a few days. However, when very vulnerable people are infected with particular Salmonella strains, instead of developing a simple gastrointestinal infection, the bacteria enter their bloodstream and cause serious complications such as sepsis.

This is a big problem globally, but especially across sub-Saharan Africa. This is because there are populations who are at greater risk of developing severe disease, predominantly children with chronic malaria infection and malnutrition, as well as adults with advanced HIV infection. Unfortunately, this creates a ‘perfect storm’ in which Salmonella becomes a life-threatening infection with a high mortality rate. Across Africa, it’s one of the commonest bugs that we’ve isolated from blood cultures (a test used to detect bacteria or fungi in a person’s blood). Even though it is very widespread, it doesn’t have the same profile as other tropical infections.

Essentially, we want to develop a human challenge model that can be used to test and accelerate vaccines for this disease. There are currently a couple of vaccines that are being tested in Phase I studies. Our study will aim to determine the lowest possible dose of bacteria needed for the majority (three-quarters) of volunteers to meet the criteria for diagnosis. Once the optimal dose is established and we can demonstrate that our model is safe, it can be replicated in future to test different vaccines.

We’ve gained a lot of knowledge about Salmonella infection from animal models, and these continue to provide us with valuable insights. However, there are fundamental questions around how these vaccines work in humans that we need to answer in order to advance their development. Establishing a human infection model will allow us to add to the body of data that has been generated by animal models and to assess vaccines in a way that is relevant to regulatory bodies.

The study will also provide us with insights into how Salmonella causes disease and how the immune system responds to infection in different individuals.

Q: How long will the study last and how will it work?

The whole project will run for three years – one year for setup, one year to run the trial itself, and one year for lab work and analysis. We are proposing to recruit a group of between 20 and 80 healthy volunteers who will be deliberately infected with a particular strain of Salmonella. In this study, we will be looking at two different strains – one which was isolated in Malawi and we believe to be associated with invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease, and one non-invasive strain which most commonly causes diarrhoea.

Subject to ethical approval, we are hoping to start recruiting to the study in January 2023. All volunteers will go through a detailed screening process which will include taking a full medical history, blood tests, an ultrasound and a physical exam. We will also do a consent quiz, which is designed to ensure that each volunteer fully understands what they are consenting to and what the study involves. When a volunteer has passed the screening, we will give them a tour of the study facility a week before they participate in the challenge and run through the whole process with them.

On the day of the challenge itself, the volunteer will be admitted to the facility and given a solution of water and bicarbonate of soda which has been inoculated with a dose of bacteria. After they have consumed this, they will remain in the facility for about seven days, and we will continue to monitor them every day for two weeks. This will include collecting daily blood and stool samples. When a volunteer develops specific symptoms or has met the endpoint criteria, we will start antibiotic treatment to halt the infection.

Volunteers will be monitored 24/7 and there will be an on-call medical team in the unlikely event that someone requires urgent medical attention. It’s important to point out that this is a treatable infection – we will always have access to the appropriate antibiotics if needed.

There’s then a follow-up period for up to a year. We will check in with volunteers at one month, 90 days, six months and finally a year after the challenge. However, volunteers will always be able to get in touch with us for additional check-ins if they are experiencing any issues.

Q: How will you determine the right dose of bacteria to use?

This is a dose-escalation study, so our primary aim is to identify the lowest dose needed for three-quarters of volunteers to meet the criteria for diagnosis. We’ll start by using a low dose, which is informed by the doses used in other, similar human challenge studies in the past. Depending on the number of volunteers who meet the criteria, we will either stick with using this dose or increase it slightly until we meet our target.

Q: What criteria will you be using to decide whether someone has Salmonella infection?

What we define as ‘disease’ and the ‘endpoint’ criteria is absolutely critical to how the model will be used. Depending on where you set the bar, you’ll get very different outcomes. We could say that the endpoint is a volunteer shedding Salmonella in their stool and presenting with a specific set of symptoms. Alternatively, you might be looking for a bloodstream infection, which would set the bar higher.

We are in the process of working out where to draw that line. One of the first actions we’ll take as part of this project is to convene a consultation group. This group will include a broad range of stakeholders including vaccine manufacturers, policymakers and key experts. While we could determine the criteria for ourselves, we want to make sure that this model and the data produced are useful to everyone.

Q: Can you explain why the study needs to use healthy volunteers, rather than volunteers who may be more representative of the populations most impacted by Salmonella infection?

There’s always a trade-off when you are designing a human challenge model. The bottom line is that the study needs to be as safe as possible, and we need to minimise the risks posed to volunteers. That often means using participants drawn from a population who may not be the most exposed to the pathogen you are studying.

From an ethical perspective, we also need our volunteers to be healthy adults who can fully understand what participating in the study entails and give informed consent. The consent process is very rigorous which means ultimately you need to exclude lots of people, because either they are not medically fit enough to take part, or there may be concerns around their understanding of what the study involves. All of this means that we necessarily need to take a step or two back from the main population of interest – vulnerable infants in sub-Saharan Africa.

Ultimately, it’s called a model for a reason. It doesn’t exactly replicate what you would get in a field setting, but it provides an important stepping stone to testing a Phase I vaccine in a safe and effective way.

Q: Who else will you be working with to develop and run the study?

The study will be led by Imperial, but we will be working closely with partners at PATH (a global non-profit organisation aimed at improving public health), the University of Liverpool, the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome (MLW) unit and the University of Oxford. Together, we will work to develop the strains of Salmonella used in the study, which will be manufactured at a dedicated facility in the USA.

Human challenge studies are an important area of work within the Department of Infectious Disease and the Infection and AMR theme of the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. Our NHS partners within the Imperial College Academic Health Science Centre (AHSC) are key to delivering this work and in particular, we will be working with the NIHR BRC Imperial Patient Experience Research Centre (PERC) on an extensive package of public engagement and involvement activities building on their expertise developed on other challenge models.

This project presents a great opportunity for all of our partners to share their expertise and to bring everyone together in collaboration. Hopefully, this is the first step in producing something that has a truly global impact.

Source: Imperial College London