Valentina Tagliapietra, Flavia Riccardo, Martina Del Manso and Giovanni Rezza

E-CDC risk status: endemic

(data as of October 31, 2022)

History and current situation

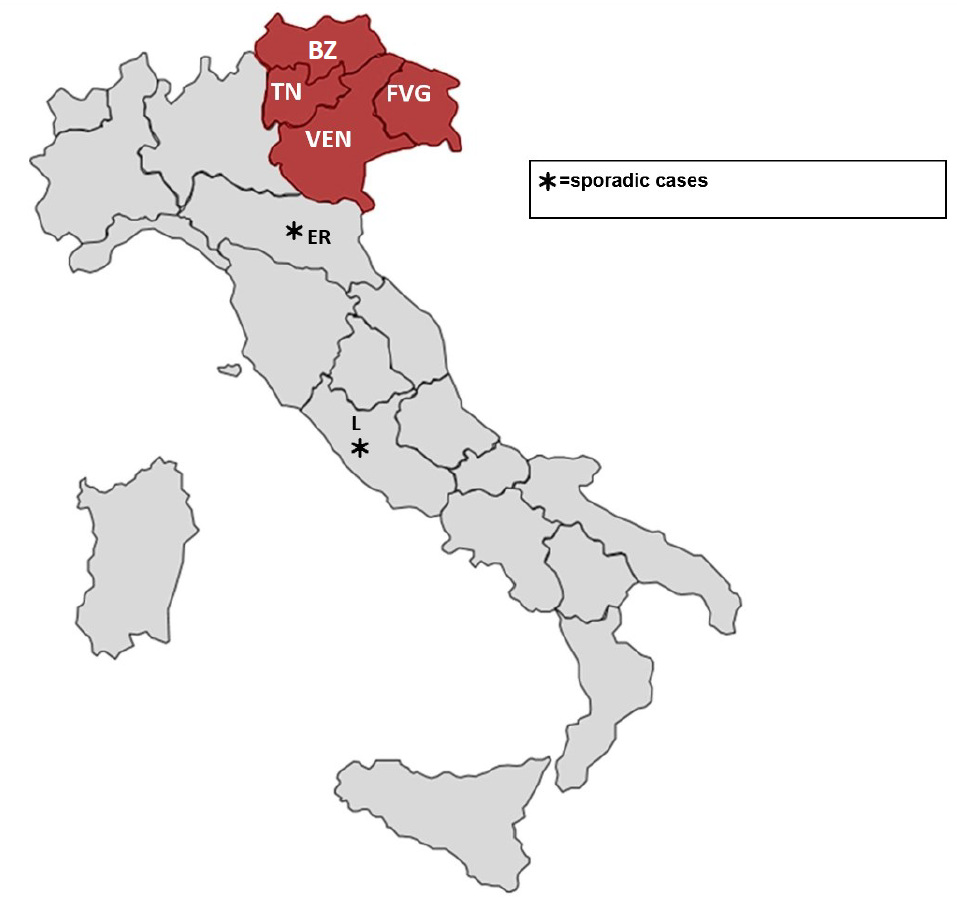

Italy is considered a low-incidence country for tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) in Europe.1 Areas at higher risk for TBE in Italy are geographically clustered in the forested and mountainous regions and provinces in the north east part of the country, as suggested by TBE case series published over the last decade.2-5 A national enhanced surveillance system for TBE has been established since 2017.6 Before this, information on the occurrence of TBE cases at the national level in Italy was lacking. Both incidence rates and the geographical distribution of the disease were mostly inferred from endemic areas where surveillance was already in place, ad hoc studies and international literature.1

TBE has been recorded in Italy since 1967, with foci of infection in north east (Trento, Belluno and Gorizia) and central (Florence and Latina) provinces.7-10 TBE presence in central Italy has not been confirmed by further studies on ticks and serosurveys conducted afterwards,11-12 suggesting the extinction of these small endemic foci.

Serological investigations of people at risk such as forestry rangers, hunters and mushrooms collectors, have been performed in order to get information on TBE virus (TBEv) circulation in the pre-alpine and alpine regions reporting seroprevalence values of 0.6%, 1.07% and 3.2% in Friuli-Venezia Giulia,13 Trento province14 and Turin province,15 respectively. Interestingly, Turin province has never reported human cases of TBEV infection, so far.

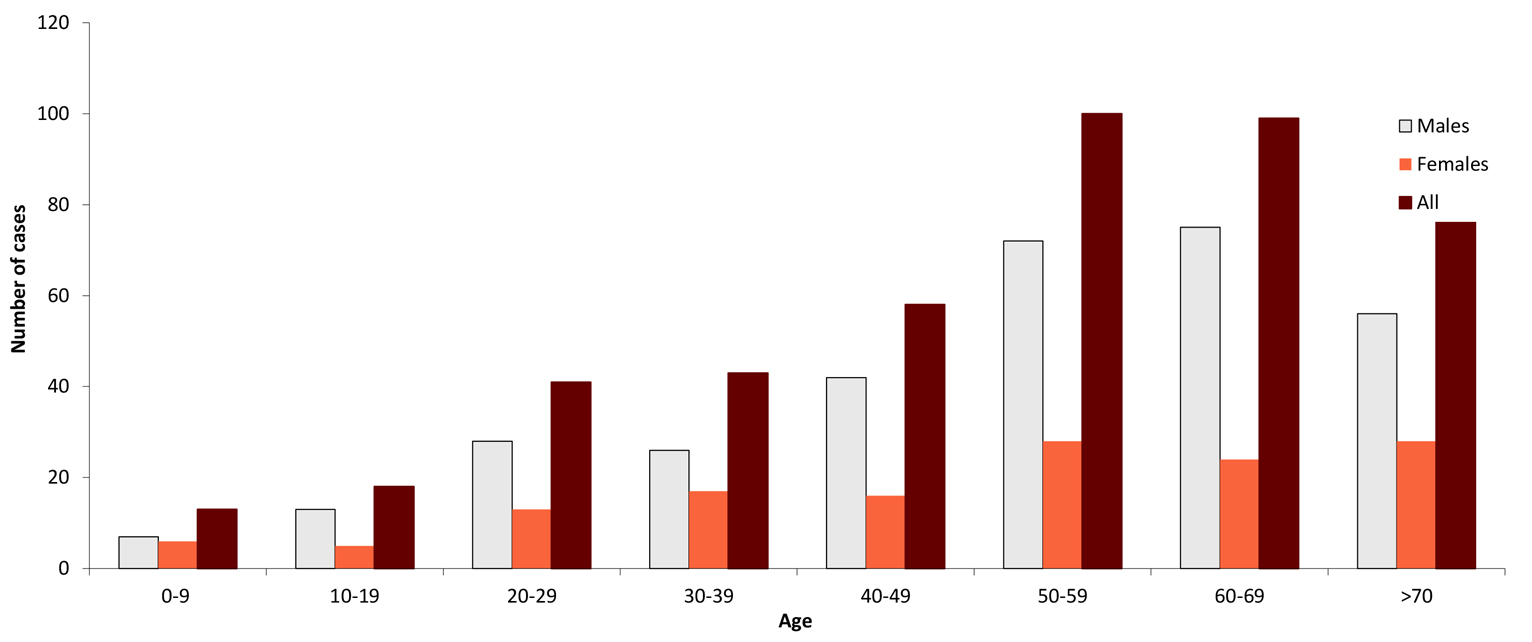

A retrospective study conducted in 2015 in the north east regions, allowed the identification of 367 cases (0.38 per 100,000 inhabitants) during the period from 2000 to 2013. TBE cases were mainly males (70%), and around 70% of them were between 30 and 70 years of age. A significant increase in the annual incidence rate (IR) was observed during the study period, from 0.18 per 100,000 in the year 2000 up to 0.59 per 100,000 in 2013 (incidence rate ratio [IRR]=1.05 per 1 calendar year increase, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–1.08, P>0.01). The majority of identified TBE cases occurred between April and October, consistent with the seasonality of tick activity. Areas with IR greater than 10 per 100,000 appear to be concentrated in 3 main foci: 1 in the Autonomous Province of Trento (IR=41.6), 1 in the Belluno Alps in Veneto (IR=35.9), and the third at the extreme north east section of Friuli-Venezia Giulia (IR=42.6).3 According to this study, the risk of TBE is associated with altitude, with the highest values found for municipalities between 400 and 600 m a.s.l., and the IR falling along with municipality altitude decrease or increase. Of note, the IR for municipalities with a mean altitude >800 m a.s.l. appears to be 5 times higher than for municipalities with a mean altitude <200 m a.s.l..3

A national TBE surveillance system recording neuro-invasive TBEV infections was established since 2017. In 2020, the number of notified cases reached a record, with 55 cases mainly from four northeastern Italian regions and provinces: Trento, Bolzano, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Veneto (Fig. 3). In addition to these well-known positive areas, another two regions were added although they reported intermittent sporadic cases, namely Emilia Romagna with 2 cases in 2020 and Lazio with 1 case in 2019 (Fig. 3). Average annual incidence per 100.000 inhabitants doubled its value from 0.77 in 2017 to 1.42 in 2020. In particular, the province of Trento showed a sharp increase in the incidence since 2012, despite vaccination efforts. To assess the current risk of infection in the provincial territory, an integrated one-health research approach was applied, combining the analysis of the distribution of human cases, the study of seroprevalence in sentinel hosts (goats) and the direct screening of questing ticks.16 A total of 1.56% of goats resulted positive for specific antibodies for TBEV. Sampling of ticks was concentrated in areas where TBEV circulation was observed both in seropositive goats or in humans, resulting in a prevalence of 0.17%. In particular these results revealed an increased prevalence of TBEV in ticks and the emergence of new active TBE foci which are located northward and at higher altitude (1.109 m a.s.l.) compared to previous investigations. None of the areas with seropositive goats was confirmed by TBEV detection in ticks and recent human cases, but this aspect needs further confirmation.

The observed increase of TBE cases was associated with the expansion of tick populations resulting from climatic factors, increasing abundance of ungulates, and changes in human behavior and land use, in addition to increased recognition and reporting of TBE cases.22-23 Although the distribution of human cases is consistent with that of the competent tick vector, the widely dispersed distribution of ticks in the environment and their very low TBEV prevalence (usually below 1%), make them an unsuitable indicator of TBEV infection risk. For these reasons, entomological studies, even if performed in endemic regions, cannot be translated into a direct human risk, and other factors should be considered in order to address public health efforts toward TBE hazard. For example, since the 1990s, rising cervid population numbers and changes in forest structure in the northeastern regions and provinces of Italy were observed in conjunction with an increase in TBE incidence,22 but this relationship is not always positive and at a threshold density level of ungulates TBEV prevalence decreases.24 Transmission of TBEV from infected nymphs to co-feeding uninfected ticks on rodents is considered the most efficient route for this virus, therefore, studies regarding the ecological and abiotic conditions affecting tick feeding dynamics are important. Recently a long-term longitudinal field study highlighted that the autumnal cooling rate and the presence of roe deer and mice are crucial ecological drivers for co-feeding transmission which in turn reflect in the maintenance of a TBE hotspot.25

Vaccination for TBE is currently recommended in Italy among residents and occupationally exposed groups, in particular in rural endemic areas.17 In affected regions and provinces, TBE is offered free of charge to risk groups and the resident population since 2013 in Friuli-Venezia Giulia and since 2018 in the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano. Affected regions and provinces have also made information on TBE vaccination available on websites.18-21

In conclusion, the incidence of TBE in Italy is relatively low, and the risk appears to be geographically restricted to the pre-alpine and alpine regions of the country. More studies are necessary to disentangle the complex factors that are involved in the circulation and maintenance of TBEV in an endemic focus and early-warning predictors should be better assessed. Human cases are currently reported from northeastern regions (Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto and in the Provinces of Trento and Bolzano), with the highest incidence rates being reported in areas between 400 and 600 m a.s.l. TBE vaccine is offered to resident people living in high-risk areas, but its impact on disease occurrence in the affected communities is not yet evaluated.

Overview of TBE in Italy

| Table 1: Virus, vector, transmission of TBE in Italy (Northeastern) | |

|---|---|

| Viral subtypes, distribution | European TBEV subtype; northeast regions: Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Trentino-Alto Adige (Figure 3) |

| Reservoir animals | Ticks and small rodents. Consumption of milk and milk products from infected goats, sheep, or cows |

| Infected tick species (%) | Ixodes |

| Dairy product transmission | Not documented |

| Table 2: TBE-reporting and vaccine prevention in Italy (northeastern) | |

|---|---|

| Mandatory TBE reporting6,16 |

Reported by Department of Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health, Italy in collaboration with all the Infectious Diseases Units and Public Health Districts. Case definition: clinical criteria are any symptoms of inflammation of the CNS (for example, meningitis, meningo-encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, encephaloradiculitis). A TBE case is confirmed by at least one of the following five laboratory criteria: TBE specific IgM AND IgG antibodies in blood; TBE specific IgM antibodies in CSF; seroconversion or four-fold increase of TBE-specific antibodies in paired serum samples; detection of TBE viral nucleic acid in a clinical specimen; isolation of TBE virus from clinical specimen. Surveillance has been enhanced at the national level since 2017. |

| Special clinical features13-15 |

Biphasic disease is not reported. At-risk groups are defined by occupational risk (i.e. agricultural workers and forest or lumber workers) or risk hobbies (i.e. hiking/trekking, mushroom foraging).Presumed place of exposure and date of tick bite are recorded.Sequelae (information available on 193 cases): 18.1% with permanent sequelae, and 28.5% with temporaryCase-fatality rate: 0.7% |

| Available vaccines |

TICOVAC 0.5 mL (Pfizer Srl) |

| Vaccine recommendations and reimbursement, and uptake by age group/risk group/ general population |

Friuli-Venezia Giulia: vaccination is free of charge for residents. Veneto: Vaccination is not free of charge. Recommended for those who live in the woods or in rural areas at risk for TBE. Trentino-Alto Adige: vaccination is free of charge for residents. |

| Name, address/website of TBE National Reference Center |

Prof. Giovanni Rezza Dipartimento Malattie Infettive Istituto Superiore di Sanità Viale Regina Elena, 299 00161 Roma, ItaliaWebsite: https://www.iss.it/?p=27 |

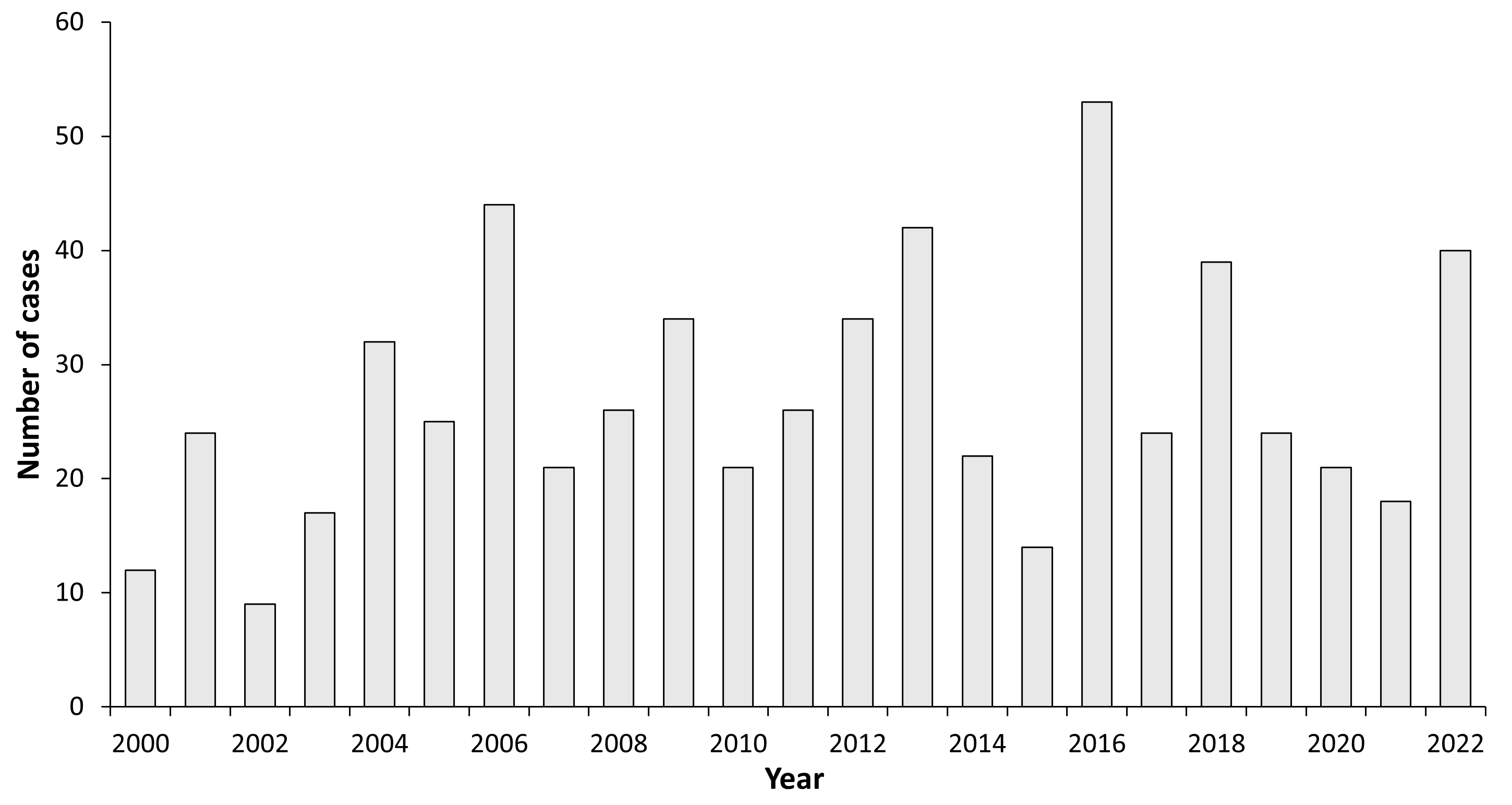

Figure 1: Reported human cases of TBE, Italy, 2000–202226-28

Source data:

| Year | Number of Cases | Incidence / 105 | Vaccination rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 12 | 0.021 | |

| 2001 | 24 | 0.042 | |

| 2002 | 9 | 0.016 | |

| 2003 | 17 | 0.029 | |

| 2004 | 32 | 0.055 | |

| 2005 | 25 | 0.043 | |

| 2006 | 44 | 0.074 | 0.11 |

| 2007 | 21 | 0.035 | 0.11 |

| 2008 | 26 | 0.043 | 0.11 |

| 2009 | 34 | 0.056 | 0.14 |

| 2010 | 21 | 0.035 | 0.13 |

| 2011 | 26 | 0.044 | 0.16 |

| 2012 | 34 | 0.057 | 0.10 |

| 2013 | 42 | 0.069 | 0.18 |

| 2014 | 22 | 0.036 | 0.15 |

| 2015 | 14 | 0.023 | |

| 2016 | 53 | 0.087 | |

| 2017* | 24 | 0.04 | |

| 2018* | 40 | 0.065 | |

| 2019* | 37 | 0.04 | |

| 2020* | 55 | 0.035 | |

| 2021** | 18 | 0.03 | |

| 2022*** | 40 | 0.068 |

** 18 total with 4 imported cases

*** Total cases from January 1, 2022 to October 31, 2022

Note: Data on vaccine coverage are not available for 2015–2022

Figure 2: Age and gender distribution of reported human cases of TBE, Italy, 2000–2016

| Age group (years) | Males | Females | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-9 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| 10-19 | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| 20-29 | 28 | 13 | 41 |

| 30-39 | 26 | 17 | 43 |

| 40-49 | 42 | 16 | 58 |

| 50-59 | 72 | 28 | 100 |

| 60-69 | 75 | 24 | 99 |

| >70 | 56 | 28 | 84 |

Figure 3: Regions in northeastern Italy reporting TBE cases (BZ=Autonomous Province of Bolzano; TN=Autonomous Province of Trento; [BZ+TN=Trentino-Alto Adige] VEN= Veneto; FVG= Friuli-Venezia Giulia; ER=Emilia Romagna; L=Lazio).

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Maria Grazia Caporali, Francesca Farchi and Catia Valdarchi for their support in data collection and analysis.

Contact

valentina.tagliapietra@fmach.it

Citation:

Tagliapietra V, Riccardo F, Del Manso M, Rezza G. TBE in Italy. Chapter 12b. In: Dobler G, Erber W, Bröker M, Schmitt HJ, eds. The TBE Book. 6th ed. Singapore: Global Health Press;2023. doi:10.33442/26613980_12b15-6

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Tick-borne encephalitis. In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2016. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018.

- Beltrame A, Ruscio M, Cruciatti B, et al. Tickborne encephalitis virus, northeastern Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(10):1617-9.

- Rezza G, Farchi F, Pezzotti P, et al. Tick-borne encephalitis in north-east Italy: a 14-year retrospective study, January 2000 to December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2015;20. doi:10.2807/1560- 7917.ES.2015.20.40.30034.

- Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia. L’encefalite da zecca (TBE) in Friuli Venezia Giulia. http://www.regione.fvg.it/rafvg/export/sites/default/RAFVG/salute-sociale/zecche/allegati/TBE_FVG.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi Sanitari Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Malattie trasmesse da zecche in Trentino. https://www.apss.tn.it/documents/10180/96314/Malattie+trasmesse+da+zecche+in+Trentino+aprile+2018/d5b15609-df3c-4286-90b9-f52e5ffff4b5?version=1.1. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Ministero della salute. Piano nazionale di sorveglianza e risposta all’encefalite virale da zecche e altre arbovirosi. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=3399. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Amaducci L, Arnetoli G, Inzitari D, Balducci M, Verani P, Lopes MC. Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) in Italy: report of the first clinical case. Riv Pat Nerv Ment. 1976;97:77-80.

- Paci P, Leoncini F, Mazzotta F, et al. Meningoencefaliti da zecche (TBE) in Italia. Ann Sclavo. 1980;22:404-16.

- Verani P, Ciufolini, MG, Nicoletti L. Arbovirus surveillance in Italy. Parassitologia. 1995;37:105–8.

- Ciufolini MG, Verani P, Nicoletti L, Fiorentini C, Bassetti D, Mondardini V, Caruso G. Recent advances in the eco‐epidemiology of tick borne encephalitis in Italy. Alpe Adria Microbiology Journal. 1999;8:81–3.

- Tomao P, Ciceroni L, D’Ovidio MC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi and to tick- borne encephalitis virus in agricultural and forestry workers from Tuscany, Italy. Eur J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:457-63.

- Di Renzi S, Martini A, Binazzi A, et al. Risk of acquiring tick- borne infections in forestry workers from Lazio, Italy. Eur J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:1579-81.

- Cinco M, Barbone F, Grazia Ciufolini M, et al. Seroprevalence of tick-borne infections in forestry rangers from northeastern Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:1056-61.

- Cristofolini A, Bassetti D, Schallenberg G. Zoonoses transmitted by ticks in forest workers (tick-borne encephalitis and Lyme borreliosis): preliminary results. Med Lav. 1993;84(5):394-402.

- Pugliese A, Beltramo T, Torre D. Seroprevalence study of Tick-borne encephalitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Dengue and Toscana virus in Turin Province. Cell Biochem Funct. 2007;25(2):185-8.

- Alfano N, Tagliapietra V, Rosso F, Ziegler U, Arnoldi D, Rizzoli A. Tick-borne encephalitis foci in northeast Italy revealed by combined virus detection in ticks, serosurvey on goats and human cases. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):474-484. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1730246.

- Piano Nazionale di Prevenzione Vaccinale 2017-2019. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata di Trieste. Informazioni per la vaccinazione contro l’encefalite da morso di zecca http://www.asuits.sanita.fvg.it/opencms/export/sites/ass1/it/_materiale_informativo/docs/vaccinazioni-informazioni/vacc-TBE.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Regione del Veneto. Vaccino anti-encefalite da zecche (TBE). https://www.vaccinarsinveneto.org/scienza-conoscenza/vaccini-disponibili/vaccino-anti-encefalite-da-zecche-tbe.html. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Provincia Autonoma di Trento. https://www.ufficiostampa.provincia.tn.it/Comunicati/Vaccino-contro-l-encefalite-da-zecca-gratis-dal-1-gennaio. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Azienda Sanitaria dell’Alto Adige. Dipartimento di Prevenzione. http://www.asdaa.it/prevenzione/attualita.asp?news_action=4&news_article_id=614941. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- Rizzoli A, Hauffe HC, Tagliapietra V, Neteler M, Rosà R. Forest structure and roe deer abundance predict tick-borne encephalitis risk in Italy. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4336. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004336.

- Kunze U; ISW-TBE. Report of the 20th annual meeting of the International Scientific Working Group on Tick-Borne Encephalitis (ISW-TBE): ISW-TBE: 20 years of commitment and still challenges ahead. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10(1):13-17. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.08.004.

- Cagnacci F, Bolzoni L, Rosà R, Carpi G, Hauffe HC, Valent M, Tagliapietra V, Kazimirova M, Koci J, Stanko M, Lukan M, Henttonen H, Rizzoli A. Effects of deer density on tick infestation of rodents and the hazard of tick-borne encephalitis. I: empirical assessment. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42(4):365-72. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.02.012

- Rosà R, Tagliapietra V, Manica M, Arnoldi D, Hauffe HC, Rossi C, Rosso F, Henttonen H, Rizzoli A. Changes in host densities and co-feeding pattern efficiently predict tick-borne encephalitis hazard in an endemic focus in northern Italy. Int J Parasitol. 2019;49(10):779-787. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2019.05.006.

- National Institute of Statistics. Demo – Demographic Statistics. Istat. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://demo.istat.it/

- Del Manso M, Caporali MG, Bella A, et al. Arbovirosi in Italia – TBE Rapporto Annuale 2021. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/arbovirosi/bollettini

- Del Manso M, Caporali MG, Bella A, et al. Arbovirosi in Italia – TBE N. 1 – Novembre 2022. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/arbovirosi/bollettini