Jana Kerlik

E-CDC risk status: Endemic

(data as of end 2022)

History and current situation

The former Czechoslovak Republic was one of the first countries in Europe where the tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) was identified. This discovery was made in 1947, when Rampas and Gallia observed a high incidence of disease identified as “Czechoslovakia encephalitis”, and TBEV was isolated from Ixodes ricinus.1

In 1951, for the first time ever, and again in Czechoslovakia, the alimentary transmission of TBEV from infected animals to humans was confirmed during a large outbreak in Rožňava. There were 271 hospitalized and serologically confirmed tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) patients. Blaškovič et al. found that most patients had drunk milk from the local dairy, which did not comply with basic sanitary requirements. The milk had not been pasteurized, but only stirred, equalized, and distributed. In addition, the goat milk that had been supplied to the dairy was also possibly infected.2 During the examination of the tick-borne encephalitis TBE focus in Rožňava, the goats were found with high anti-TBEV titers.3

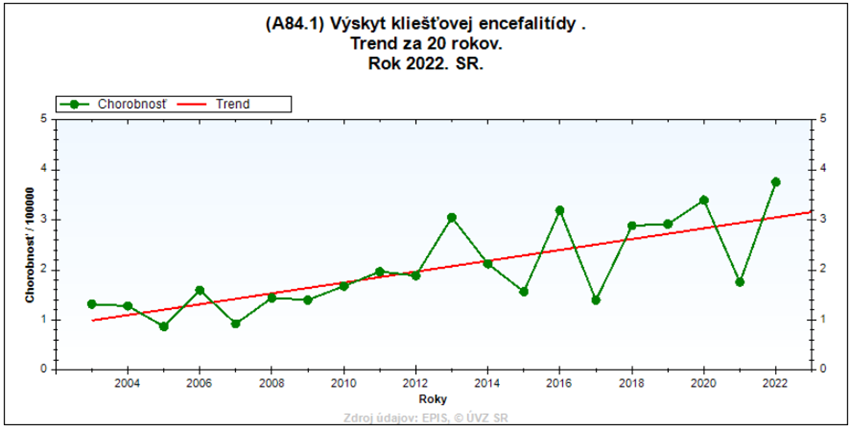

In the last few years, we have observed an increasing trend of TBE cases in Slovakia, for which there are several potential contributing factors. First, tick populations thrive because of extreme temperatures, high humidity, and the presence of snow cover during the winter, which acts as insulation. Early springs, as well as summers that are not too hot or dry, may also be important positive factors for tick survival and reproduction success. Other factors are ecological, demographic, and socioeconomic conditions (for instance, changes in land usage such as increased forestation or newly created gardens, and the growing popularity of outdoor pursuits such as hiking and fishing).4 Slovakia is well known in Europe for TBE alimentary outbreaks. Over the last few years, there has been a growing trend in the number of food-borne TBE outbreaks. Slovaks like to consume products made from raw goat and sheep milk. Moreover, raw goat milk has been recently promoted as a product to improve health and immunity in humans. In one case, a patient under immunosuppressive therapy in Slovakia drank raw goat milk in order to improve his health status, and he died from TBE.5

According to Decree No 585/2008 Coll. of the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic, which defines details on prevention and control of communicable diseases, TBE vaccination is compulsory for employees of virological laboratories working with TBE virus and TBE vaccination is recommended for occupationally exposed persons (forest workers, students of forestry schools, agriculture workers, etc.). Some insurance companies partially reimburse TBE vaccine in Slovakia.6,7

*Note: Readers may also wish to review the accompanying chapter for the Czech Republic, given the geographic proximity and national history of these countries.

Overview of TBE in Slovakia

| Table 1: Virus, vector, transmission of TBE in Slovakia | |

|---|---|

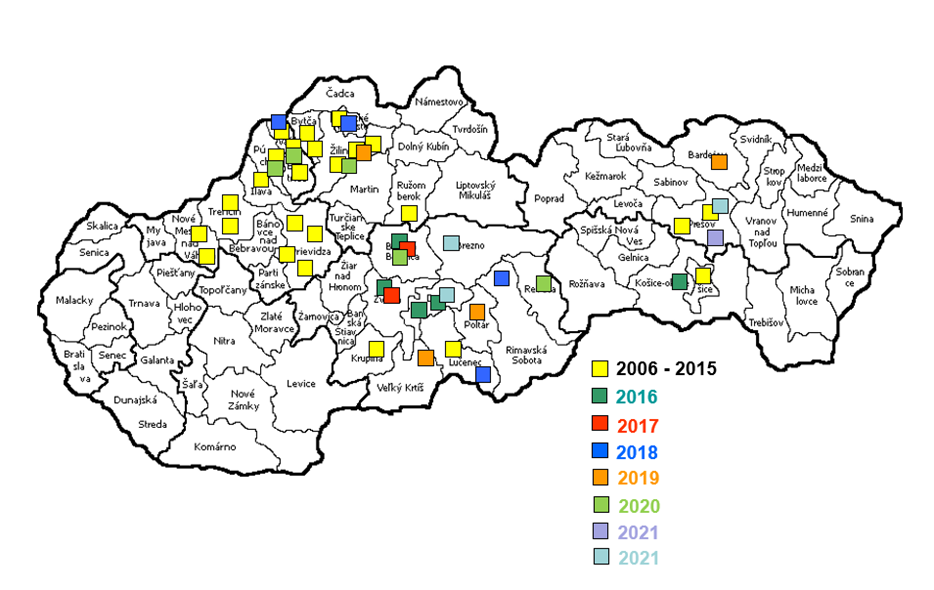

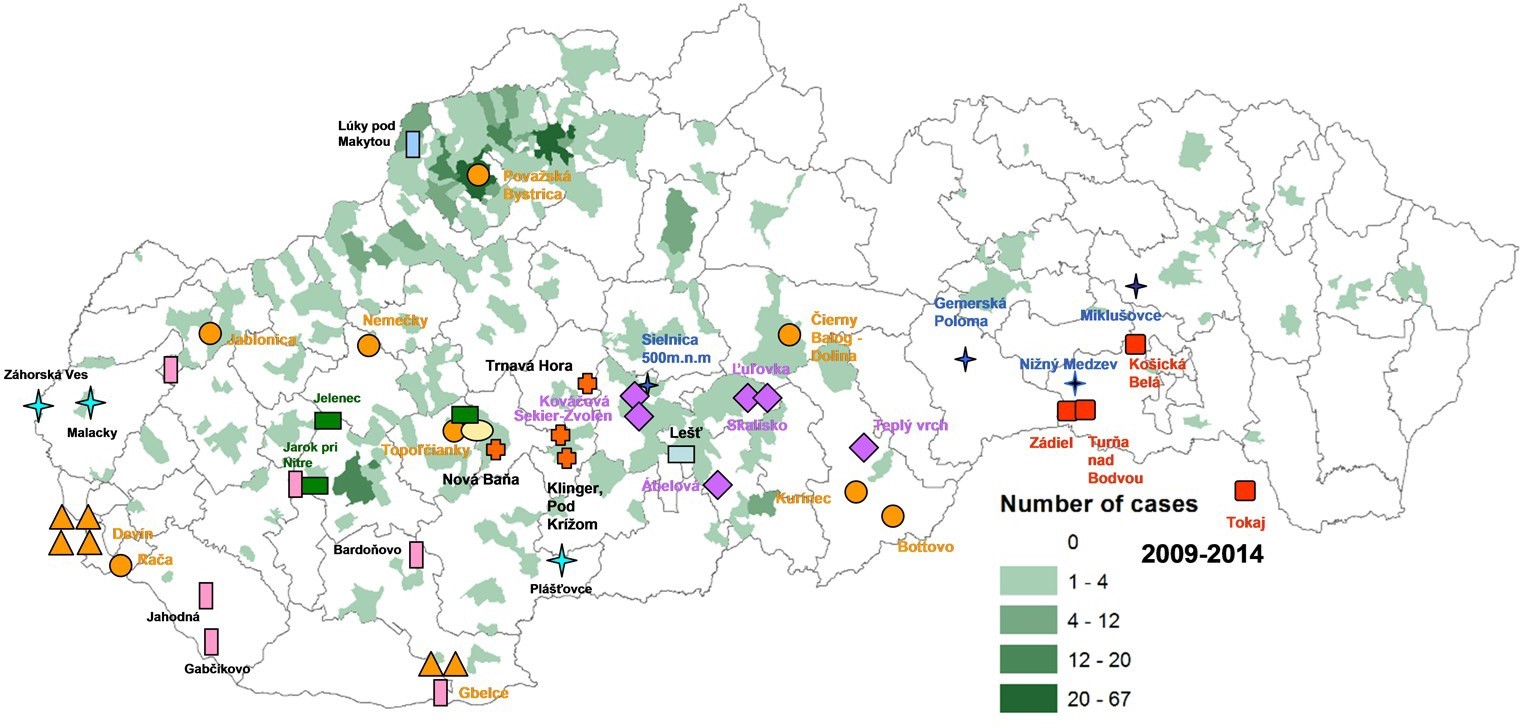

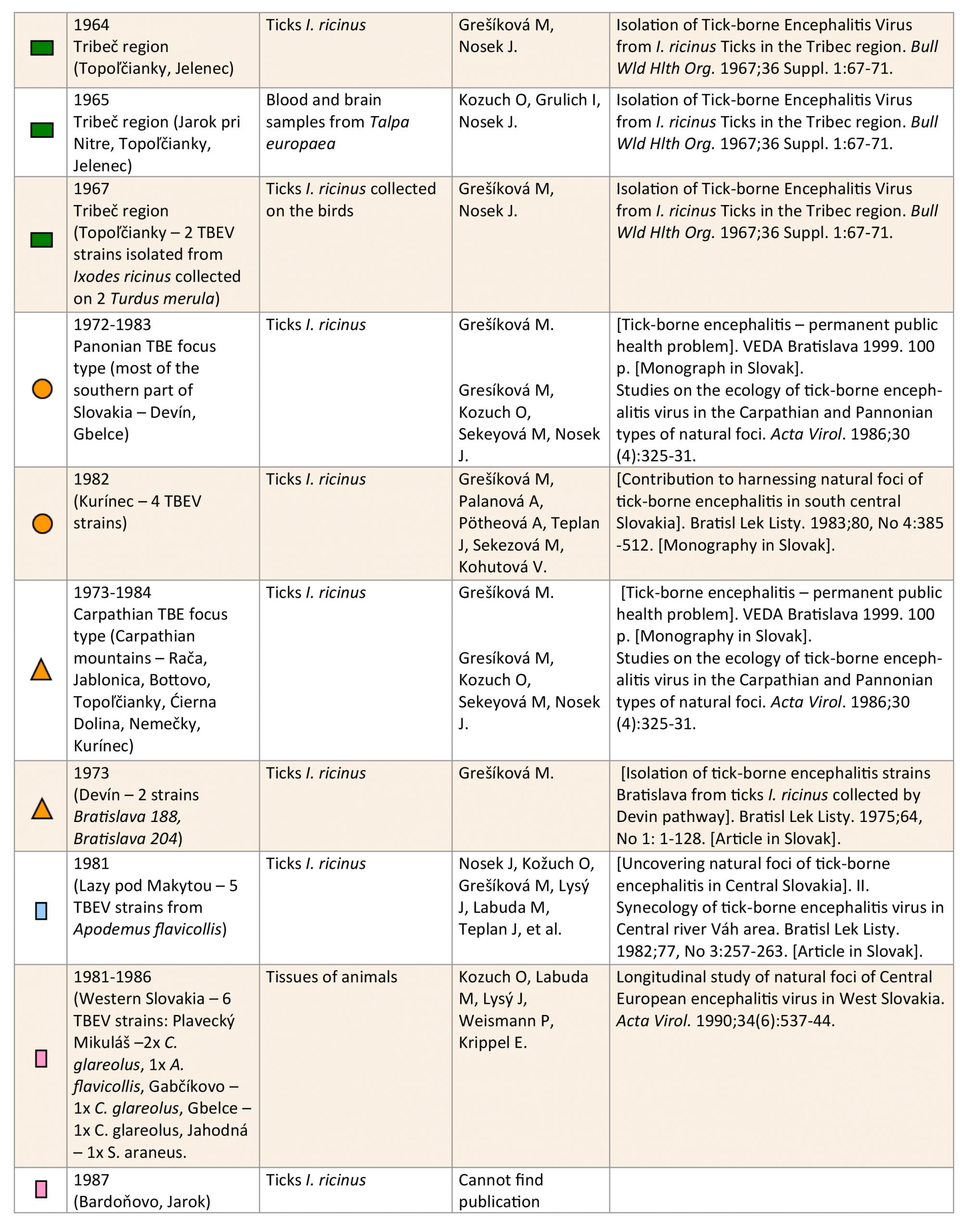

| Viral subtypes, distribution | European subtype1 At present, there are around 50 known endemic TBE foci in Slovakia. A list of natural foci of TBE in Slovakia was developed by the Public Health Authority of Slovakia in 2002 directly on the basis of virus isolation data from ticks and reservoir animals in the years 1964–1997 from the Institute of Virology, Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava as well as indirectly, by inference about the site of infection in patients with TBE as reported during 1972–2002.8 In recent years there has been a shift of natural TBE foci from the southern to the northern areas of the country.9 In the last few years, we have observed an increasing trend of TBE incidence.10 |

| Reservoir animals | Tribeč region (Jarok pri Nitre, Jelenec, Topoľčianky), 1965: Out of 46 blood and brain samples taken from moles (Talpa europaea), 7 positive isolations of TBEV were obtained. Therefore, moles can represent not only an important host animal, but may also be considered a reservoir of TBEV in elementary foci11

Tribeč region, 1967: Isolation of virus from the blood of Apodemus flavicollis, Clethrionomys glareolus, and Erinaceus roumanicus12 Tribeč region, 1967: 2 TBEV strains were isolated from Ixodes ricinus collected on 2 Turdus merula13 Lúky pod Makytou, 1981: 5 strains of TBEV isolated from ticks and organs of Apodemus flavicollis (in 15% infected)14 Western Slovakia (6 localities), 1981–1986: 6 TBEV strains isolated from organs of C. glareolus (4), Apodemus flavicollis (1), Sorex araneus (1)15 Záhorská Ves, 1990–1992: 8 TBEV isolates from organs of C. glareolus (6), Apodemus flavicollis (1), Apodemus sylvaticus (1)16 Košická Belá, 2013: TBEV from the brain sample of Buteo buteo17 |

| Infected tick species (%) | The number of infected ticks in endemic areas varies widely from 0.1% to 5% depending on the season and habitat18 Tribeč, 1964: On average, 0.2% of ticks were infected by TBEV in the entire Tribeč region. When only elementary foci were taken into account, this proportion increased to 0.4% (Topoľčianky) and 0.8% (Jelenec)18

Záhorská Bystrica, 1965: 1.7% of female ticks infected by TBEV19 Devín, 1973: 0.1% of nymphs and 1.1% of female ticks infected by TBEV20 Slovakia, 1981: In Slovakia there are 2 types of TBEV natural foci – Carpathian and Pannonian. In Carpathian natural TBEV foci, there were 2.6% of ticks infected by TBEV. In the Pannonian natural TBEV foci, there were 0.1% of ticks infected by TBEV21 Kurínec, 1982: 0.8% of nymphs and 6% of male ticks (I. ricinus) in south-central Slovakia22 Carpathian and Pannonian types of TBE natural foci, 1972–1982: The proportion of infected ticks in both types of natural foci was 1.7% in total. In Carpathian elementary foci (ranging from 0.4% to 4.1%; average of 2.5% of ticks were infected). In Pannonian elementary foci (ranging from 0.07% to 6.0%; average of 0.9% of ticks were infected)23 Western and Central Slovakia, 1980–1984: Western Slovakia, April–July 1980 (0.7%), May 1984 (0.1%), Central Slovakia April– May 1982 (0.2%)24 Western Slovakia, 1985–1990: In Slovakia surveillance of TBEV in ticks, carried out during 1985–1990 by the Virology Institute of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, showed that the TBEV distribution rates among ticks ranged from 0.30% (Jarok, Bardoňovo in 1987) to 0.38% (Malacky in 1990) in the 25 sites in the western region (data not published) Žiar nad Hronom, Banská Štiavnica a Žarnovica, 2002–2007: In the small sample of 142 ticks tested, there were 4.98% infected with TBEV25 |

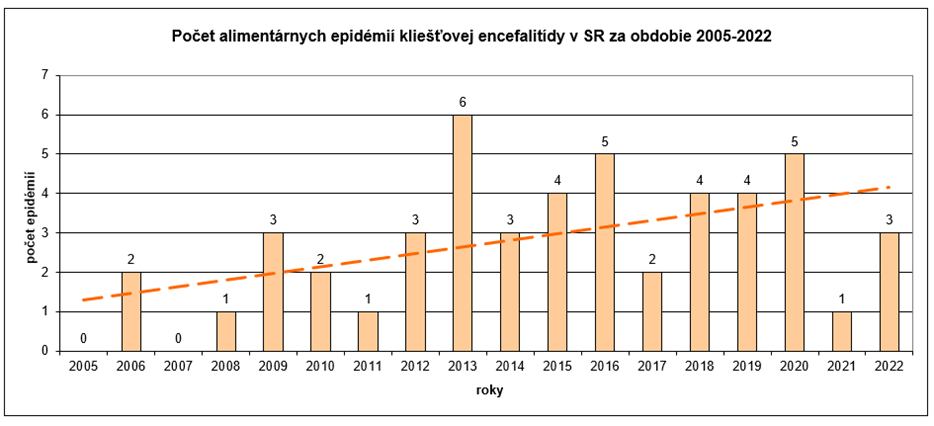

| Dairy product transmission | During 2007–2016 we observed a growing trend in the number of TBE outbreaks. A total of 26 outbreaks (those with 2 or more people) were responsible for 142 TBE cases (13.9%) in the studied period. There were 13 family outbreaks with at least 2 linked TBE cases in a single outbreak. Larger outbreaks with 3 or more cases were recorded 13 times. The highest number of outbreaks (6) was recorded in 2013 (4 family outbreaks, 2 large outbreaks). In 2016, there was the largest number of TBE cases (44) reported in a single outbreak over the past 30 years.10 The most probable and also confirmed common factor in the transmission of TBEV during outbreaks was goat milk and its products (61.5%, 16 outbreaks). Sheep’s milk and products have caused probably 7 outbreaks (26.9%) and cow’s milk was the probable cause of 2 TBE outbreaks (7.7%). In one TBE outbreak, the probable TBE transmission factor was reported to be mixed goat and sheep milk.10

In the majority of outbreaks (22) the probable transmission factor of TBEV was identified epidemiologically. Sheep cheese was considered as the TBEV transmission factor in the TBE outbreak with the highest number of TBE cases (44) over the past 30 years by retrospective case control study.26 In 4 outbreaks TBEV was serologically confirmed in goats. In 3 outbreaks TBEV was tested directly in sheep milk. In 1 outbreak the sheep milk was TBEV positive, however it was not the milk from which the incriminated cheese was made. In another 2 outbreaks TBEV was not found in the sheep milk. 2018 again was a peak year for alimentary transmission: In 5 outbreaks altogether 21 TBE cases were recorded: 3x from consumption of sheep cheese, 1x from consumption of goat cheese, 1x from consumption of goat milk; in all cases the TBEV was detected in milk |

| Table 2: TBE reporting and vaccine prevention in Slovakia | |

|---|---|

| Mandatory TBE reporting | According to Slovak legislation, physicians, hospitals, national reference centers, and laboratories are obliged to report TBE cases comprehensively via paper-based forms, e-mails, or by phone (more urgent) to the individual Regional Public Health Authorities, which passes the information to the Epidemiological Information System (EPIS), or they can report TBE cases directly to EPIS.6 (§ 4) The TBE case definition set by Commission Implementing Decision (August 8, 2012) was adopted in Slovakia at the end of 2012.26

• Possible case: Not applicable • Probable case: Any person meeting the clinical criteria (fever, aseptic meningitis/encephalitis) and the laboratory criteria for probable case OR Any person meeting the clinical criteria with an epidemiological link • Confirmed case: Any person meeting the clinical criteria (fever, aseptic meningitis/encephalitis) and laboratory criteria for case confirmation |

| Other TBE-surveillance | No data available |

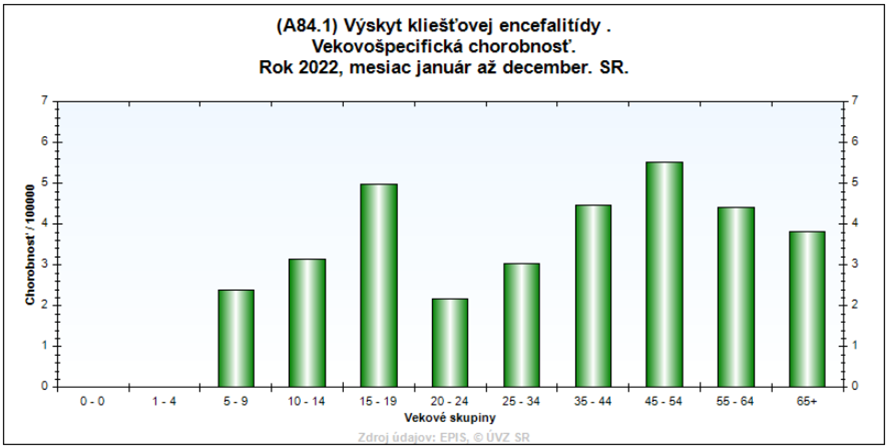

| Special clinical features | Note: In the TBE search interface, EPIS offers the following categories: meningeal form (includes biphasic form, but also encephalitis), febrile form, and neurological form (paresis). If greater specification is desired, each case must be reviewed individually for details such as course of disease, which is quite complicated given the large number of cases. Meningeal form (including encephalitis): 68.5%10 Febrile form: 21.8%10 Other neurological form: 8.8%10 Asymptomatic form (during outbreak): 0.2%10 Unspecified report: 0.7%10 The meningeal form of the disease was observed in almost the same ratio after alimentary transmission and tick-borne transmission (66.3% vs 69.1%). The febrile form affected 24.9% patients after consumption of TBE infected milk products and 20.9% tick-bitten patients. Most TBE cases were recorded among retired persons (19.7%). High-risk occupations were identified in 15.3%, including general workers (111), foresters (17), farmers (12), field workers (9), and railway workers (7).10 Other groups affected by TBE: students (9.1%), unemployed persons (8.0%), and children (6.6%). Other professions (e.g., women on maternity leave, food producers, health professionals, educators, social workers and others) were affected by the disease in 33.1% of cases.10 |

| In most TBE cases (85.9%) a recovery was observed. In 6 cases, permanent consequences (palsy, neurological complications) were recorded. Three cases resulted in death (0.3% mortality). In 2 cases, an infectious cause was involved; in 1 case death was from another cause. In 13.2% of cases the impact of the disease was not specified.10 In a study, we have diagnosed post-encephalitic syndrome in 27.2% of patients who most often reported headache, tremor of upper limbs, fatigue, and lack of concentration.28 | |

| Available vaccines | FSME IMMUN; FSME IMMUN junior |

| Vaccination recommendations and reimbursement | According to the law, employees of the virology laboratories in Slovakia that work with TBEV must be vaccinated6 (§ 8, section 5) Vaccination is recommended in persons who are professionally exposed to increased risk of selected diseases such TBE. Physicians usually vaccinate subjects who are forestry and water management (including students of forestry schools) employees, agricultural workers, surveyors, geologists, tourist hiking guides, employees of the mountain hunts and lifts, employees of recreation facilities, members of police forces and customs officers, professional soldiers and reserve soldiers called for extraordinary service, and employees performing work associated with the operation and maintenance of the railway tracks.6 (§ 10, section 2)

Some insurance companies partially reimburse TBE vaccine in Slovakia.7 |

| Vaccine uptake by age group/ risk group/ general population | TBE immunization data on the Slovak population are not available, but according to numbers of sold vaccine doses and child immunization control, the estimated vaccination coverage in Slovakia is 1% (1.3/100,000)10 None of the TBE patients seen in the country during the period 2007–2016 has had all 3 vaccine doses. Most cases were not vaccinated (98.8%). In 9 (0.9%) cases, a vaccination record was not found or was not available. Partial vaccination was recorded in 3 cases.10 |

| Name, address/website of TBE National Reference Center | NRC for arboviruses and haemorrhagic fevers Public Health Authority of Slovakia Trnavská cesta 52

826 45 Bratislava Slovakia elena.ticha@uvzsr.sk |

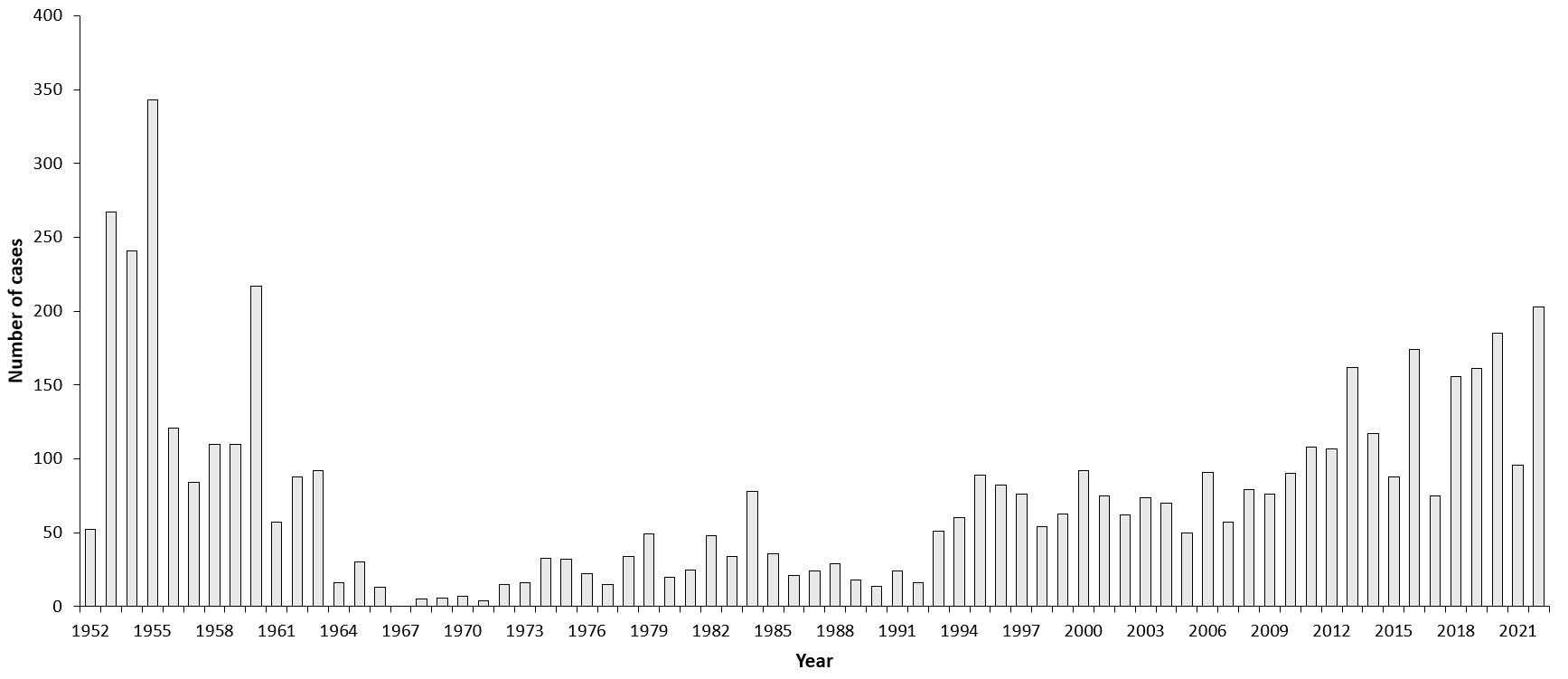

Figure 1: Burden of TBE in Slovakia over time1

| Year | Number of cases | Incidence / 105 |

|---|---|---|

| 1952 | 52 | 1.5 |

| 1953 | 267 | 7.4 |

| 1954 | 241 | 6.6 |

| 1955 | 343 | 92 |

| 1956 | 121 | 3.2 |

| 1957 | 84 | 2.2 |

| 1958 | 110 | 2.8 |

| 1959 | 110 | 2.8 |

| 1960 | 217 | 5.4 |

| 1961 | 57 | 1.4 |

| 1962 | 88 | 2.1 |

| 1963 | 92 | 2.1 |

| 1964 | 16 | 0.4 |

| 1965 | 30 | 0.7 |

| 1966 | 13 | 0.3 |

| 1967 | not available | not available |

| 1968 | 5 | 0.1 |

| 1969 | 6 | 0.1 |

| 1970 | 7 | 0.2 |

| 1971 | 4 | 0.1 |

| 1972 | 15 | 0.3 |

| 1973 | 15 | 0.3 |

| 1974 | 33 | 0.7 |

| 1975 | 32 | 0.7 |

| 1976 | 22 | 0.5 |

| 1977 | 15 | 0.3 |

| 1978 | 34 | 0.7 |

| 1979 | 49 | 1 |

| 1980 | 20 | 0.4 |

| 1981 | 25 | 0.5 |

| 1982 | 48 | 1 |

| 1983 | 34 | 0.7 |

| 1984 | 78 | 1.5 |

| 1985 | 36 | 0.7 |

| 1986 | 21 | 0.4 |

| 1987 | 24 | 0.5 |

| 1988 | 29 | 0.6 |

| 1989 | 18 | 0.3 |

| 1990 | 14 | 0.3 |

| 1991 | 24 | 0.5 |

| 1992 | 16 | 0.3 |

| 1993 | 51 | 1.07 |

| 1994 | 60 | 1.1 |

| 1995 | 89 | 1.6 |

| 1996 | 82 | 1.5 |

| 1997 | 76 | 1.4 |

| 1998 | 54 | 1 |

| 1999 | 63 | 1.17 |

| 2000 | 92 | 1.71 |

| 2001 | 75 | 1.39 |

| 2002 | 62 | 1.15 |

| 2003 | 74 | 1.38 |

| 2004 | 50 | 0.93 |

| 2005 | 50 | 0.93 |

| 2006 | 91 | 1.69 |

| 2007 | 57 | 1.06 |

| 2008 | 79 | 1.46 |

| 2009 | 76 | 1.4 |

| 2010 | 90 | 1.66 |

| 2011 | 108 | 1.99 |

| 2012 | 107 | 1.98 |

| 2013 | 162 | 2.99 |

| 2014 | 117 | 2.16 |

| 2015 | 88 | 1.62 |

| 2016 | 174 | 3.21 |

| 2017 | 75 | 1.38 |

| 2018 | 156 | 2.87 |

| 2019 | 161* | 2.95 |

| 2020 | 185** | 3.39 |

| 2021 | 96*** | 1.76 |

| 2022 | 203**** | 3.74 |

1952–1996: Grešíková M. [Tick-borne encephalitis – permanent public health problem]. VEDA Bratislava 1999, p 62. [Monograph in Slovak].

1997–2022: [Epidemiologický informačný systém] [Internet] Epidemiological Information System; 2022 [Cited 2023 Feb 20]. Data export 2006–2022. Available at: www.epis.sk [In Slovak].

There were 161 TBE cases in 2019. There were 4 alimentary outbreaks:

- 2 cases – goat milk

- 2 cases – goat milk (cheese)

- 3 cases – goat milk

- 7 cases – goat milk (cheese)

There were 9 sporadic cases, where the transmission mechanism was ingestion of milk/cheese of goat and sheep origin.

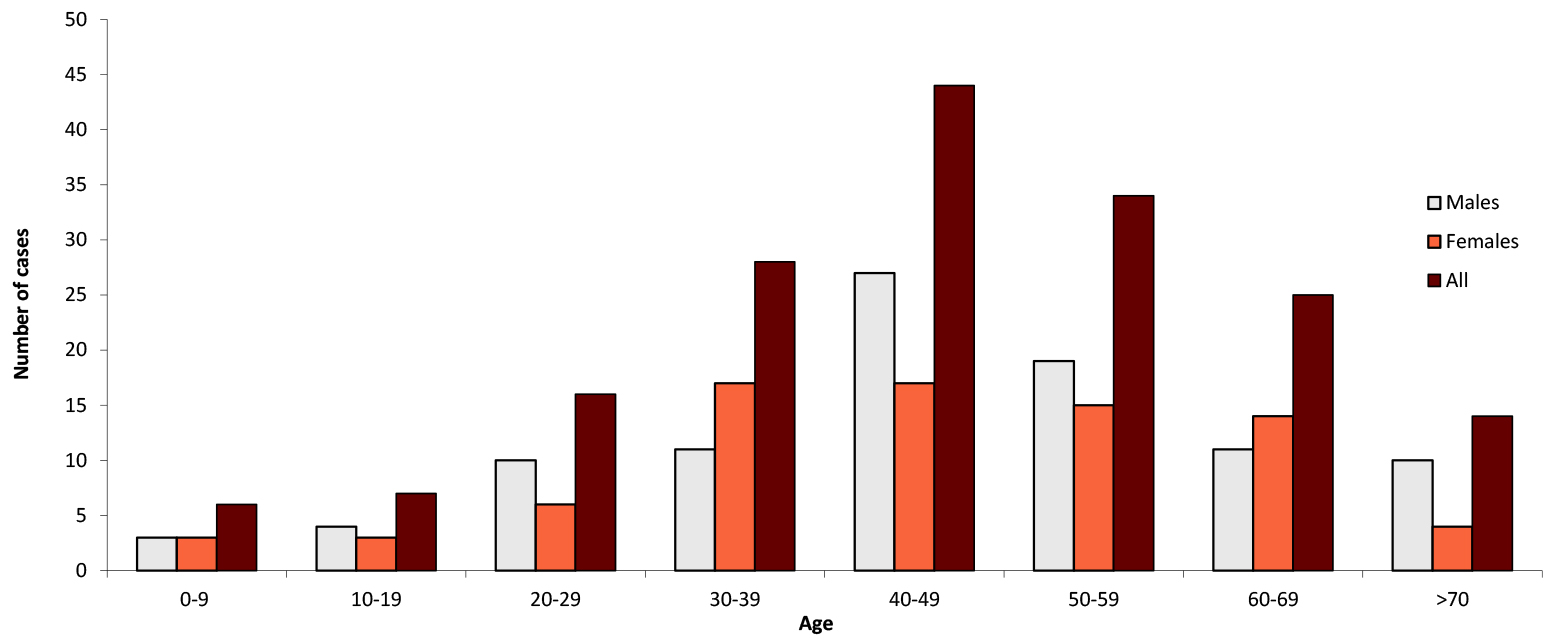

Figure 2: Age and gender distribution of TBE in Slovakia, 2016

| Age group | Males | Females | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-9 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 10-19 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 20-29 | 10 | 6 | 16 |

| 30-39 | 11 | 17 | 28 |

| 40-49 | 27 | 17 | 44 |

| 50-59 | 19 | 15 | 34 |

| 60-69 | 11 | 14 | 25 |

| >70 | 10 | 4 | 14 |

[Epidemiologický informačný systém] [Internet] Epidemiological Information System; 2017 [Cited 2017 Jan 5]. Data export 2015. Available at: www.epis.sk [In Slovak].

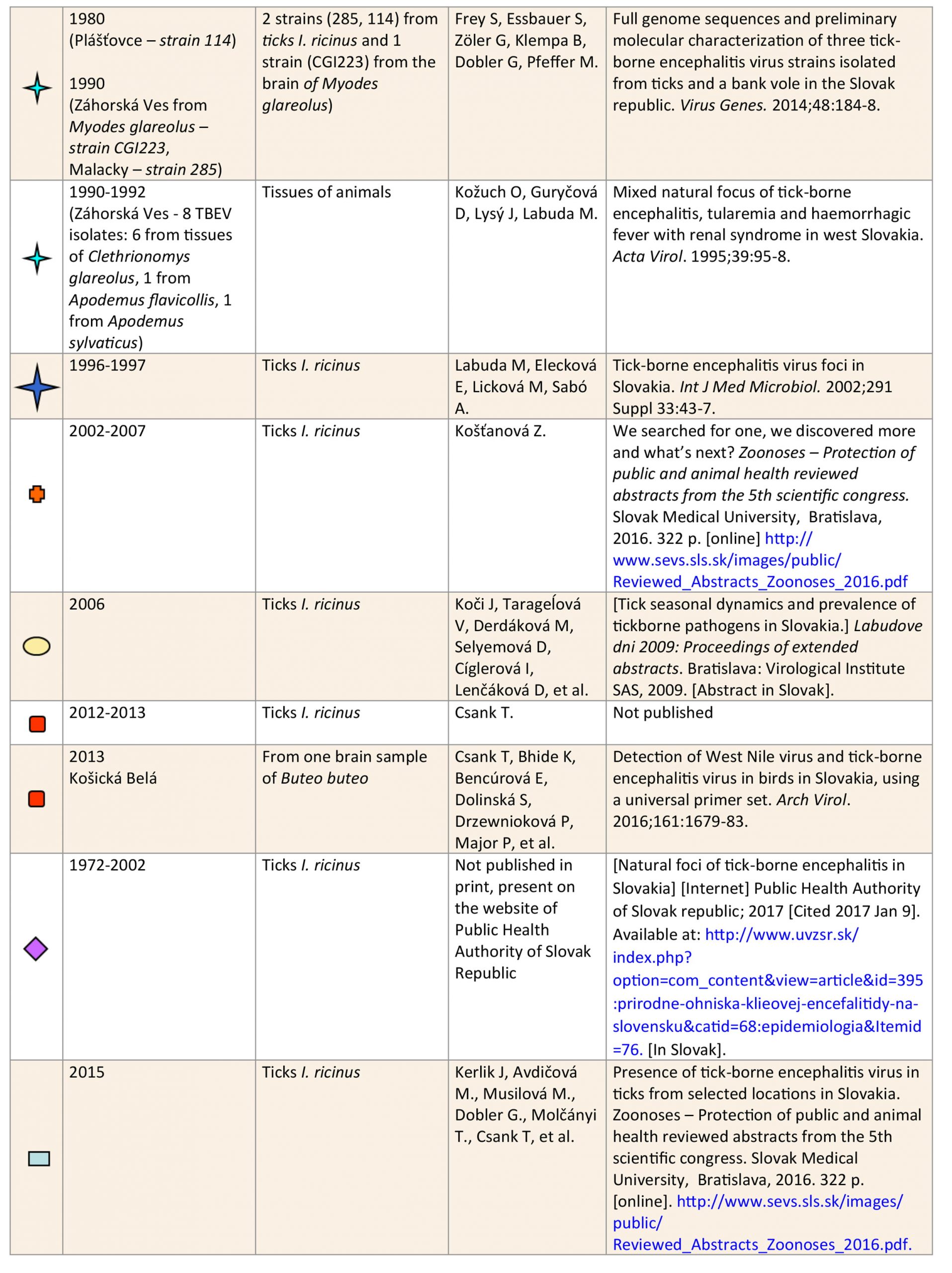

Figure 3: TBEV isolation (1972–2015) and TBE cases (2009–2014) in Slovakia

Contact:

Citation:

Kerlik J. TBE in Slovakia. Chapter 12b. In: Dobler G, Erber W, Bröker M, Schmitt HJ, eds. The TBE Book. 6th ed. Singapore: Global Health Press; 2023. doi: 10.33442/26613980_12b29-6

References

- Rampas J, Gallia F. [Isolation of tick-borne encephalitis virus from ticks Ixodes ricinus]. Čas Lék Čes. 1949;88:1179-80.[Article in Czech].

- Blaškovič D. [Outbreak of encephalitis in Rožňava natural focus of infections]. Bratislava: VEDA SAV, 1954. 314 p. [Article in Czech].

- Bárdoš V, Hanzal F, Havlík O, et al. [Csechoslovak tick-borne encephalitis]. Praha: Státní zdravotnické nakladatelství, 1954. 92 p. [Monograph in Czech].

- Dorko E, Rimárová K, Kizek P, Stebnický M, Zákutná L. Increasing incidence of tick-borne encephalitis and its importance in the Slovak Republic. Cent Eur J Public Health.2014;22:277-81.

- Štefkovičová M, Kopilec Garabášová M, Šimurka P, Oleár V. Familiar occurrence of tick-borne encephalitis in endemic region – case study. Zoonoses – Protection of public and animal health reviewed abstracts from the 5th scientific congress. Slovak Medical University, Bratislava, 2016. 322 p. [online]. Available at: http://www.sevs.sls.sk/images/public/ Reviewed_Abstracts_Zoonoses_2016.pdf.

- [Decree No. 585/2008 Coll. of the Ministry of Health of the Slovak Republic, which defines details on prevention and control of communicable diseases]. Zbierka zákonov SR. 2008 Dec 10;Pt 202:5024-41. [In Slovak].

- [Vaccination against tick-borne encephalitis] [Internet] Dôvera; 2017 [Cited 2017 Jan 5]. Available at: http://www.dovera.sk/ poistenec/tema-lieky-a-zdravotnicke-pomocky/a1801/ockovanie-proti-kliestovej-encefalitide. [In Slovak].

- [Natural foci of tick-borne encephalitis in Slovakia] [Internet] Public Health Authority of Slovak Republic; 2017 [Cited 2017 Jan 9]. Available at: http://www.uvzsr.sk/ index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=395:prirodne-ohniska- klieovej-encefalitidy-na-slovensku&catid=68:epidemiologia&Itemid=76. [In Slovak].

- Lukan M, Bullova E, Petko B. Climate Warming and Tick-borne Encephalitis, Slovakia. Emerg Inf Dis. 2010;16:524-6.

- [Epidemiologický informačný systém] [Internet] Epidemiological Information System; 2017 [Cited 2017 Jan 5]. Data export 2007–2016. Available at: http://www.epis.sk. [In Slovak].

- Kozuch O, Grulich I, Nosek J. Serological survey and isolation of tick-borne encephalitis virus from the blood of the mole (Talpa europaea) in a natural focus. Acta Virol. 1966;10:557-60.

- Kozuch O, Gresíková M, Nosek J, Lichard M, Sekeyová M. The role of small rodents and hedgehogs in a natural focus of tick-borne encephalitis. Bull World Health Organ. 1967;36 Suppl:61-6.

- Ernek E, Kozuch O, Lichard M, Nosek J. The role of birds in the circulation of tick-borne encephalitis virus in the Tribec region. Acta Virol. 1968;12:468-70.

- Nosek J, Kožuch O, Grešíková M, et al. [Uncovering natural foci of tick-borne encephalitis in Central Slovakia]. II. Synecology of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Central river Váh area. Bratisl Lek listy. 1982;77:257-63. [Article in Slovak].

- Kozuch O, Labuda M, Lysý J, Weismann P, Krippel E. Longitudinal study of natural foci of Central European encephalitis virus in west Slovakia. Acta Virol. 1990;34:537-44.

- Kožuch O, Guryčová D, Lysý J, Labuda M. Mixed natural focus of tick-borne encephalitis, tularemia and haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in West Slovakia. Acta Virol. 1995;39:95- 8.

- Csank T, Bhide K, Bencúrová E, et al. Detection of West Nile virus and tick-borne encephalitis virus in birds in lovakia, using a universal primer set. Arch Virol. 2016;161:1679-83.

- Grešíková M, Nosek J. Isolation of Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus from Ixodes ricinus Ticks in the Tribec region. Bull World Health Organ. 1967;36(Supp 67-71).

- Grešíková M, Kožuch O, Nosek J. Die rolle von Ixodes ricinus als Vektor des Zeckenencephalitis Virus in verschiedenen mitteleuropäischen Naturherden. Zentralbl Bakteriol Orig. 1968;207:423-9.

- Grešíková M. [Isolation of tick-borne encephalitis strains Bratislava from ticks Ixodes ricinus collected by Devin pathway]. Bratisl Lek Listy. 1975;64:1-128. [Article in Slovak].

- Grešíková M. [Tick-borne encephalitis – permanent public health problem]. VEDA Bratislava 1999, p 62. [Monograph in Slovak].

- Grešíková M, Palanová A, Pötheová A, Teplan J, Sekezová M, Kohutová V. [Contribution to harnessing natural foci of tick- borne encephalitis in the south central Slovakia]. Bratisl Lek Listy. 1983;80:385-512. [Article in Slovak].

- Gresíková M, Kozuch O, Sekeyová M, Nosek J. Studies on the ecology of tick-borne encephalitis virus in the Carpathian and Pannonian types of natural foci. Acta Virol. 1986;30:325-31.

- Grešíková M; Sláčiková M, Kožuch O. Tick-borne encephalitis in Slovakia during years 1980-1984. Bratisl Lek Listy. 1987;88:358-65. [Article in Slovak].

- Košťanová Z. We searched for one, we discovered more and what’s next? Zoonoses – Protection of public and animal health reviewed abstracts from the 5th scientific congress. Slovak Medical University, Bratislava, 2016. 322 p. [online]. Available at: http://www.sevs.sls.sk/images/public/Reviewed_Abstracts_Zoonoses_2016.pdf.

- Tarkovská V, Seligová J, Molčányi T. [Tick-borne encephalitis outbreak with alimentary transmission in district Košice surrounding in 2016]. Collection of abstracts XXII. Červenka days, 2017;p. 17.

- Commission implementing decision of 8 August 2012 amending Decision 2002/253/EC laying down case definitions for reporting communicable diseases to the Community network under Decision No 2119/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council.

- Pertináčová J. Could tick-borne encephalitis leave behind permanent consequences? Zoonoses – Protection of public and animal health reviewed abstracts from the 5th scientific congress. Slovak Medical University, Bratislava, 2016. 322 p. [online]. Available at: http://www.sevs.sls.sk/images/public/ Reviewed_Abstracts_Zoonoses_2016.pdf.